In a previous essay I discussed the causes of the Jewish immigration wave that began in 1881 and the role of the existing Jewish population and their supporters in Britain. Here I expand on the situation of Jews in Britain before 1881, their influence on British foreign and domestic policy, the reasons for the mass immigration from 1881 onwards and the initial reactions of the more settled population to the arrival of the new, drawing on the works of Jewish historians.

Jews in Britain before 1881

A mixture of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews, amounting to 50-60,000 people, lived in Britain before the inundation from the east began, and they were remarkably free and prosperous compared to their co-religionists elsewhere.1 Todd Endelman tells us that

“The great mass of Jews, who could hardly aspire to sit in Parliament or hold a naval commission, suffered little from legal inequality. There were no restrictions on the trades they might follow, the goods in which they might trade, the areas in which they might live. Nor were they subject to special taxes, tolls, levies, or extortions. The statute book simply ignored their presence…”.2

Some legal disabilities did apply to Jews in statute but had long been enforced inconsistently. As Geoffrey Alderman describes, “professing Jews were prohibited from voting in British parliamentary elections until 1835”, after which they were on par with native Britons, but though before that date “the returning officers who supervised constituency election arrangements had the right to demand the swearing of a Christian oath by all intending voters… this was not a right they were obliged to exercise,” and some chose not to:

“In May 1830 Sir Robert Wilson told the House of Commons that Jews habitually voted in parliamentary elections in Southwark (south London) because no one bothered to insist that they take the Christian oath. In December 1832 Rabbi Asher Ansell of Liverpool was clearly able to vote in the general election without hindrance.”3

After gaining the right to vote, British Jewry was still eluded by

“...full political emancipation – meaning the right of professing Jews to stand as candidates for, and be elected to, the House of Commons. Jews were not the only religious group to be denied this right. Catholics had only won the right in 1829. Unitarians did not then enjoy the right, nor did atheists.”4

Emancipation was achieved largely thanks to the propinquity of wealthy Jews to powerful Britons. The campaign for it, as Endelman says, was “the work of a handful of ambitious, well-connected City men, whose close government contacts allowed them to put the question of Jewish disabilities on the national agenda.”5 Common British folk, and presumably the enemies of Jewry, lacked such contacts or campaigned less effectively; the successful demonstrations against the Jew Bill of 1753 were not replicated.

Overrepresentation in politics followed immediately. As Alderman describes,

“Lionel de Rothschild’s ceremonial entry into the House of Commons to take his seat (28 July 1858) was an occasion of great communal rejoicing, but it also brought into the open a worry... Jews were overrepresented in the social strata from which the political classes were drawn, and there were enough of them with sufficient private wealth to make their candidatures an attractive proposition regardless of their religious backgrounds. So the Jewish presence in the legislature grew with embarrassing speed. […] After the general election of 1865 no less than six Jews sat in the Commons; a further two were returned at by-elections during the lifetime of the 1865-8 Parliament.

Compared with the proportion which Jews comprised of the total population of the United Kingdom, they were already ‘overrepresented’ in the Commons, a state of affairs that has persisted ever since.”6

The Liberal Party was identified as the vehicle for Jewish interests. By the late 1860s,

“[w]ithout exception all the Jewish MPs at this period were Liberals. The first Jewish Conservative MP, the obscure Nottinghamshire coal-owner Saul Isaac, did not make his appearance at Westminster till 1874. Until then the parliamentary Jewish lobby was a Liberal lobby, one which had, moreover, developed during the decade (1859-68) when the Liberal party had taken on a definite form and substance, under the leadership of, first, Lord John Russell and then Gladstone. The triumphs of Liberalism and Jewish emancipation thus seemed to go hand in hand, as products of the same political ethos. On Saturday, 28 April 1866 there was a remarkable demonstration of this fact, when Russell’s Parliamentary Reform bill passed its second reading in the Commons by a majority of five votes; all six Jewish MPs voted for it, the sabbath notwithstanding.”7

Endelman shows that a degree of formal exclusion from the City of London (the financial centre) did not stop Jews trading there.8 Certainly long before 1881, Jews like the Rothschild and Mocatta families were prominent in finance, spanning bond and commodity trading to every sort of brokerage. The Rothschilds in particular were uniquely important in enabling states to borrow and, as they worked as an international partnership, their role in financing wars made their approval a factor in deciding which states could afford to fight and when.

No Jewish family, and no other family, was as rich as the Rothschilds, but Jews in general were ascendant in wealth. As Endelman says,

“At the start of the nineteenth century, most Jews in England were immigrants or the children of immigrants—impoverished, poorly educated, dependent on low-status street trades and other forms of petty commerce, popularly identified with crime, violence, and chicanery, widely viewed as disreputable and alien. Over the next three-quarters of a century, the social character of the Jewish community was transformed dramatically. Poverty ceased to be its defining characteristic. On the eve of mass migration from Eastern Europe, the majority of Jews in Britain were middle class. They were native English speakers, bourgeois in their domestic habits and public enthusiasms, full citizens of the British state, their public and personal identities increasingly shaped by the larger culture in which they lived—even if their gentile neighbors viewed them as less than fully English.”9

Geoffrey Alderman’s description is similar. In 1883,

“Over half London Jewry [the bulk of British Jewry] was now located within the middle‑classes; in 1850 the proportion had been about a third. Moreover, we know from Jacobs’ painstaking examination of commercial directories and other records that within these middle‑classes the greatest single occupational group was to be found within the financial sector—pre-eminently the Stock Exchange—followed by general merchants (over half the dealers in military stores were Jews) and certain manufacturing sectors (cigars, pipes, slippers and boots, furniture, furs, jewellery and watches, and diamonds). Jews still accounted for only 6% of London’s tailors and only 5% of London Jewry was engaged in the professions—barristers and solicitors, surgeons, dentists and architects.”10

Jews were well-positioned to influence British policy in favour of their own tribe, and they did so. They were, however, also forced to adapt to the effects of the far larger numbers of Jews entering from 1881, and in some ways were altered by it. Subsequent essays will show that British history over the subsequent century and a half has been characterised by the part-confrontation, part-collaboration of the older, more settled, more wealthy Anglo-Jewry and the later incomers from eastern Europe.

Modern Jewish Politics and foreign policy

The burgeoning of the Jewish population even before 1881 resulted in ever-growing pressure on British politicians to divert British policy in favour of Jewish interests. There has never been a body that speaks for all Jews, but several institutions constitute communal leadership with at least the tacit acceptance of a large majority of Jews in Britain. The Board of Deputies of British Jews is the most ‘central’ of these, and as early as 1836, “the Board notified the chancellor of the exchequer that it was the only official channel of communication for the secular and political interests of the Jews.”11

Throughout the 19th century, the Board and the leading families that controlled it increasingly concerned themselves with the interests of Jewry worldwide. The historian C. S. Monaco has described their practices as ‘the rise of modern Jewish politics’ and has shown how they set the pattern for the present and the past century.12 From the 1840s, Jewish interventions in foreign affairs were usually led by Sir Moses Montefiore, the long-standing president of the Board of Deputies, who famously travelled to petition for Jewish interests in several countries.

From 1871, the Board faced competition from the Anglo-Jewish Association. As Alderman describes, “[t]he Association might indeed have become a rival to the Board of Deputies”, and “[a]t first the Board of Deputies held aloof from it. But after its very effective intervention during the Balkan crisis of the late 1870s… the Board came to terms with it, and agreed in 1878 to the formation of a Conjoint Foreign Committee, consisting of seven representatives from the Board and seven from the Association.” The collaboration was productive. Jews thereafter had “an Anglo-Jewish ministry of foreign affairs” whose deliberations “were conducted in secret” and whose “conclusions were reported to neither of its constituent bodies.”13 In addition to the “close contacts” that won Jews the right to enter Parliament, the “overrepresentation” that immediately followed and the proclivities of some powerful Britons to put Jewish interests first, the secret “ministry” ensured that Jewish interests worldwide would be represented immediately and insistently in a way that had never applied to the British people or Christians.

It had become advantageous to be an ethnic minority in Britain. While Jews’ assertive internationality was rewarded, no such ministry for the native British would have been suffered to exist, let alone given any audience by the powerful. As Endelman approvingly describes,

“In Victorian Britain, at least before the end of the century, the pressures that caused Jews elsewhere to abandon traditional notions of peoplehood, collective fate, and mutual responsibility were muted. British Jews were free to express their ties to Jews abroad without fear of endangering their own struggle for civil equality and social acceptance. In this sense, the diplomatic activities of Montefiore and the Board of Deputies… testify to the confidence of communal leaders about their own status. It is important to stress this, for the contrary has been argued... Only toward the end of the century, with classical liberalism under attack and nationalism and antisemitism on the rise, did fears [of emancipation being reversed] gain ground and begin to shape communal policy—especially in regard to the newcomers from Eastern Europe.”14

Earlier in the century, Jews openly tried to steer policy their way. Later they gained reasons to hew closer in their overt conduct to the gentile elite, whose receptiveness to them was already in evidence.

Jewish foreign policy

The first professing Jewish member of Parliament, Lionel de Rothschild, probably the richest man in the world, and others of his family, used their influence in favour of the Ottoman Empire and against Europe, as did their friend and beneficiary Benjamin Disraeli. In 1876,

“Disraeli’s Eastern policy had the warm approval of most British Jews. In the first place Jews had considerable investments in Turkey, and were loath to see them thrown away because of Gladstone’s conscience. Beyond that, British Jews, in common with their co-religionists in Austria-Hungary, Germany, France, and America, looked at the situation from the point of view of Balkan Jewry. Turkish rule had allowed these Jews ‘a degree of tolerance far beyond anything conceded by Orthodox Christianity’. A. L. Green, minister of the prestigious Central Synagogue in London’s West End and ‘a Liberal in politics all my life’, instructed the Liberal Daily News ‘The Christian populations of the Turkish provinces have held, and continue with an iron hand to hold, my coreligionists under every form of political and social degradation.’”

As Alderman describes, “With very few exceptions… British Jews did not merely refuse to be associated with Gladstone’s Bulgarian Agitation; they actively opposed it.” Jewish allegiances in Britain were decided by the perceived interests of Jews at the other end of Europe. The Rothschilds became Tory supporters. “The Daily Telegraph (owned by the Jewish Levy-Lawson family) swung its influence behind Disraeli’s policy.” Then a “conference of European and American Jewish organizations” met to discuss “the reopening of the Eastern Question to improve the lot of Balkan Jewry” and soon afterward the Anglo-Jewish Association lobbied the government to amend British foreign policy. That the Ottoman forces had verifiably slaughtered thousands of Bulgarians while the Jewish organisations were merely vaguely presaging crimes against their co-religionists made no difference. “When war broke out between Russia and Turkey the following year, Sir Moses Montefiore made no secret about where his sympathies lay; he contributed £100 to the Turkish Relief Fund.”15

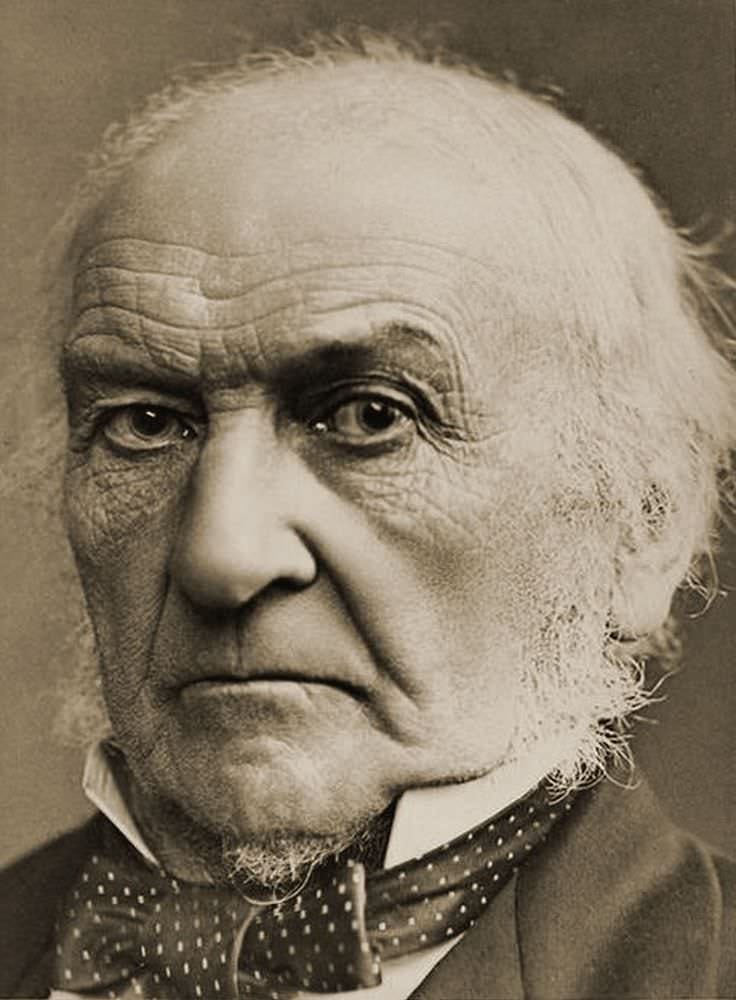

Alderman complains that “[i]t never occurred to Gladstone to consider the position of Balkan Jews, whom Turkish rule had allowed ‘a degree of tolerance far beyond anything conceded by Orthodox Christianity’.”16 Why that would occur to Gladstone is unexplained. Were Jewish interests already so sharply divergent from British ones, and on major issues? If so, was it Gladstone’s duty to side against his own people? And were Jewish politicians not loyal to Britain first? Evidently not. Then as now, Jewish politicians, activists, journalists and historians openly sided with their own tribe, wherever located, against the host nation, with scarcely any reproach, and no threat of expulsion.

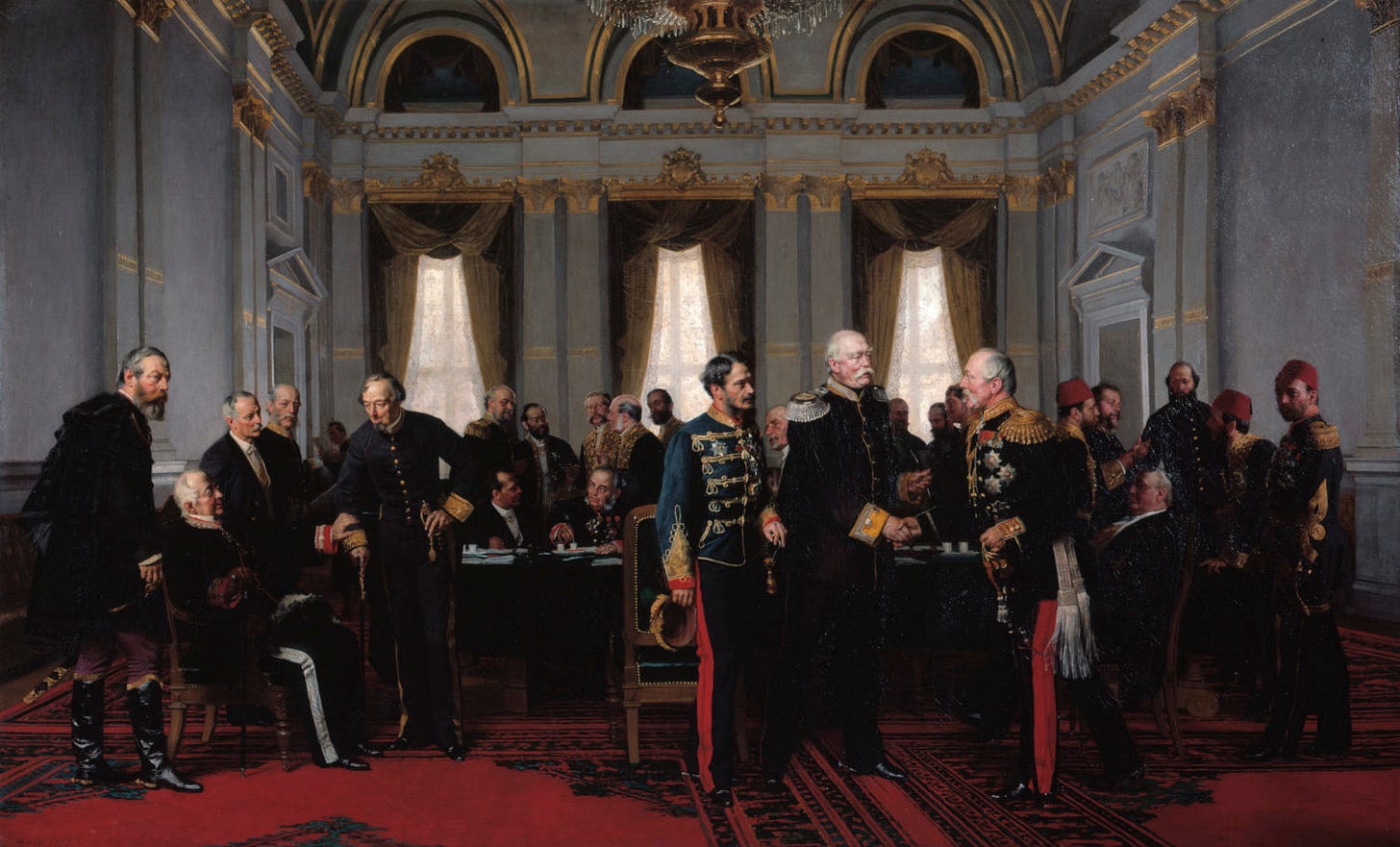

The Rothschilds’ pre-eminence as financiers of states enabled them to be represented by the two main powers at the Congress of Berlin. As Alderman describes,

“While the Anglo-Jewish Association (later in collaboration with the Board of Deputies) petitioned the British Government on the need to secure the civil and political rights of Jews in newly independent Balkan states, the aged Lionel de Rothschild mobilized the considerable resources of his extended European family, and those of his German-Jewish banking associate Gerson von Bleichröder (Bismarck’s banker and adviser) to influence proceedings at the Congress of Berlin called to resolve the crisis, and of which Bismarck was President. The result was that the western European delegates at Berlin refused to sign a final treaty until Jewish anxieties had been allayed. The Treaty of Berlin, when signed in July 1878, thus contained definite guarantees of civil and political rights for the Jews of Romania, Bulgaria, and the Danubian principalities.

For British Jewry this represented a very considerable victory; it was little wonder that when Disraeli returned in triumph from Berlin, Moses Montefiore (despite his ninety-four years) was the first to greet him at Charing Cross railway station.”17

“A very considerable victory” it was, over anyone more sympathetic to Christians than to Jews, as in the common folk of Christendom. The Congress of Berlin is spoken of by derivative historians today as a ‘triumph for Disraeli’, and it was, but for Disraeli as a Jew, not as the Prime Minister of Britain. Establishing the paradigm wherein British interests are treated as the automatic inverse of Russian (and Eastern Christian) ones was also a victory for Disraelites that continues to pay dividends today.

The Liberal Party lost Jewish electoral support, funding and candidates:

“[T]he secession of the Rothschilds had turned a great many City Jews into Conservatives, and seems to have acted as a green light to provincial Jewries also to demonstrate their support for Conservatism. This happened at Liverpool in 1876 and three years later at Sheffield, where the Conservative candidate won the support of Jews specifically because of issues of foreign policy.”18

The loss was fruitless. Disraeli had his way at Berlin anyway, the Conservative Party was accommodating, and Gladstone and the Liberals resisted Jewish demands only to the extent of causing anger, not defeat. As Alderman describes,

“the Bulgarian Agitation had had unpleasant anti-Jewish overtones, in which Disraeli’s own ethnic origins were exploited to the full, particularly by Liberal members of the intelligentsia such as Gladstone’s friend and future biographer, John Morley. Worse still, Gladstone himself had unleashed the full fury of his oratorical powers against Jews and Jewish influence. ‘I deeply deplore’, he told Leopold Gluckstein, author of a pamphlet on The Eastern Question and the Jews, ‘the manner in which, what I may call Judaic sympathies, beyond as well as within the circle of professed Judaism, are now acting on the question of the East.’”19

Gladstone’s deploration only amounted to a campaigning stance while in opposition. His own conduct of foreign policy, after he became Prime Minister in 1880, is generally agreed to have been aimless and ill-informed. And though, as Alderman notes, Gladstone refused “to become moved by the plight of Russian Jewry, or to get up an ‘agitation’ on its behalf,” it was under his premiership that the westward flood of eastern European Jews began, which led to the Jewish population of Britain quintupling by the First World War. The effects of ‘Judaic sympathies’ were multiplied in intensity by Gladstone’s own passivity toward the composition of the demos.

Reasons for mass migration

Still, it would be misleading to single out Gladstone for condemnation. Jewish immigration on a smaller scale preceded 1881. According to Endelman, “In addition to middle-class immigration from Germany, there was also a small but steady trickle of impoverished Jews from Eastern Europe—contrary to the popular myth that the pogroms of 1881 inaugurated immigration from Poland and Russia.”20 Alderman notes that “The famine in north-east Russia in 1869-70 had brought some migrants to Britain; young Jewish men, seeking to escape service in the Russian army during the war with Turkey in 1875-6, also made their way to England” before ‘the pogroms’.21 Before 1881, chain migration was underway: “as Professor Gartner has noted, a high proportion of Jewish immigrants to Britain before the 1870s appear to have been single men, without family responsibilities.' But by 1875 this pattern had broken down.”22 Simply, as Lloyd Gartner says, “emigration did not begin on account of pogroms and would certainly have attained its massive dimensions even without the official anti-Semitism of the Russian Government.”23 Endelman’s explanation is worth quoting in full:

“The most fundamental cause of emigration from Eastern Europe was the failure of the Jewish economy to grow as rapidly as the Jewish population. Between 1800 and 1900, the Jewish population of the Russian empire shot from one million to five million persons, exclusive of the one million who emigrated before the end of the century. (The Jews of Galicia, who enjoyed Habsburg tolerance but contributed to the migration current nonetheless, increased from 250,000 to 811,000.) During this same period, tsarist policy toward Jews oscillated between schemes to coerce their russification (through military service or education in state schools, for example) and measures to accomplish the reverse, that is, to isolate them from contact with sections of Russian society considered too weak to resist their alleged depredations—the peasantry, in particular. Measures with the latter goal in mind constricted Jewish economic activity and caused increasing immiseration over the course of the century. As the number of Jews exploded, the government repeatedly imposed limits on their ability to support themselves. With the exception of certain privileged persons, Jews were forbidden to live outside the Pale of Settlement, Russia’s westernmost provinces, and thus were denied access to those cities and regions where industrialization was creating new opportunities. At the same time, the government undertook steps to remove Jews from border regions and the countryside and concentrate them in the Pale’s overcrowded cities. There artisans and petty traders faced mounting competition from each other and, in the case of the former, from factory production as well. General conscription of Jewish males, imposed in 1873, as well as countless arbitrary acts of cruelty, made material immiseration seem even more unbearable.

In this context the pogroms of 1881 and the repressive legislation that followed were more catalyst than cause. Spreading fear and despair throughout Poland and Russia, they convinced the young that they had scant hope for a better future under tsarist rule. They accelerated a decades-old movement, causing migration to assume a momentum and life of its own. Personal exposure or immediate proximity to mob violence was not necessary to set people in motion. The first waves of immigrants to Britain came disproportionately from northern districts in the Pale, which were hardly touched by the pogroms of 1881. In Habsburg Galicia, which remained relatively free of pogroms throughout this period, a higher proportion of Jews migrated than in Russia. Here economic backwardness propelled migration—to Britain, the United States, and the Habsburg capital, Vienna.”24

Susan Tananbaum places more emphasis on Jews’ plight and notes that “pogroms, such as the one in Kishinev in 1903 and elsewhere, and the failure of the 1905 Revolution, provided additional impetus to leave” but agrees that “population increases and poverty had the greatest impact” and says that “[f]or several million Jews, the opportunities of the industrializing West offered their best hope for the future.”25 As Alderman says,

“most emigrants from eastern Europe were not, in the narrow sense, political refugees or, in the narrow sense, the victims of persecution. Most came from Lithuania and White Russia, where there was comparatively little anti-Jewish violence. Of course, the Russian pogroms that followed the assassination of Alexander II [in 1881], and which were renewed and intensified between 1882 and 1889, and again between 1902 and 1906, turned the trickle of Jewish refugees from Russia that had been observed before 1880 into a flood; restrictions imposed by the Russian authorities on Jewish residence, the forcing of Jews off the land while they were prohibited from living in cities, the expulsion of Jews from Moscow in 1891, all made it virtually impossible for most Russian Jews to participate in normal economic life.

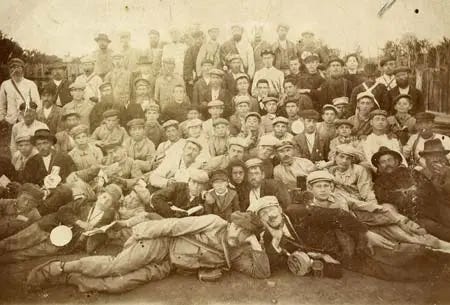

In the west, pogroms and persecutions were regarded as the basic causes of Jewish emigration. In truth the picture was much more complex. The overriding reason for Jewish emigration from eastern Europe to England was economic. During the nineteenth century the Jewish population of the Russian Empire increased from one to over six millions. Given the ever more onerous restrictions on Jewish life, this burgeoning population sought better prospects elsewhere. But the towns to which they were drawn could not support them; the flow was driven further west, and, eventually, overseas. Nor did this flow originate only in Russia or Russian Poland. The Jews of Galicia (then part of the Habsburg Empire) were politically emancipated in 1867 and were relatively persecution-free thereafter; but Jews emigrated from Galicia in greater proportion than they did from Russia. From Romania, in 1899—1900, came a stream of fusgayers (walkers), a spontaneous march across Europe by young Jews searching to escape from persecution, famine, and hopelessness.”26

Gartner describes the escalation of the migration wave:

“The turn of the century brought a decade of turmoil. In almost consecutive order, East European Jewry underwent the Rumanian ‘exodus’ of 1900, the Kishinev outrage of 1908, the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, the Revolution of 1905, and its trail of pogroms lasting into 1906. Under these hammer blows, the semblance of orderly movement which had been preserved for some ten years vanished. Waves of Rumanian wanderers, fleeing conscripts, pogrom victims, and above all, Jews who simply despaired of improvement in Russia streamed into the British Isles in proportions which bewildered those who tried to organize the flow. An added magnet was the dissolution of the “Atlantic Shipping Ring’ and that price war upon the high seas, the Atlantic Rate War from 1902 to 1904. Previously, English shippers had agreed with Continental firms that they would not sell their cheaper trans-Atlantic tickets to transmigrants. The connivances used by immigrants to outwit the shippers were abandoned and the fare dropped precipitously. Furthermore, a recognizable number of Jews from South Africa sought refuge at the commencement of the Boer War. By 1907, the great waves had spent themselves, and the Aliens Act [of 1905] erected a barrier to uncontrolled torrents.”27

Gartner characterises the easterly flood as “a spontaneous movement of people which flowed unencouraged by outsiders.”28 Yet Jews in America at the time, concerned with limiting immigration as well as helping those who had already immigrated settle, noted that “many of the refugees had been lured by extravagant promises of assistance and ‘glowing accounts of America given them by persons interested in inducing them to emigrate”.29 Many of those who settled in Britain had been in transit to America but found reasons to stop partway. Gartner himself describes how British officials in Odessa “always warned those who are proceeding to England to settle there that England is over crowded with unemployed workmen and that it is most undesirable that people should proceed there… but they invariably insist on going as their friends send them glowing accounts and also money to pay their passage.’”30

Lures

Immigration was also encouraged by and profitable for organised criminals and predators. According to Nelly Las, in large cities in Eastern Europe, “prostitution took place in certain sections known to be controlled by the Jewish underworld, to which the authorities turned a blind eye… In 1908, the American consul in Odessa reported that ‘All the business of prostitution in the city is in the hands of the Jews’.” Amid mass migration, “Jewish criminals… exported prostitution to distant lands.” Some prostitutes chose to move to wealthier countries in the expectation of earning more. Others were trafficked: “To entice their victims, Jewish sex traffickers used newspaper advertisements for jobs, the promise of an immigration certificate, and marriage proposals, all the while taking advantage of the parents’ naiveté and poverty.”31 As Tananbaum describes, “immigrants, particularly women, found travel precarious… Dishonest agents overcharged immigrants, promised them a marriage partner at the end of their journey, tricked them into the white slave trade or raped or harassed them en route.”32 Jewish women entering Britain could also be trapped into prostitution on arrival. “In the chaos of landing, the recruiter could too easily entice some friendless bewildered girls to accept hospitality at a place which would turn out to be a brothel”, according to Gartner.33

Jewish communal leaders were aware that Jews were over-represented in slavery both as victims and as perpetrators. Constance Rothschild co-founded the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women in 1885 to address the “mixture of Jewish traffickers and Jewish victims”.34 The latter were thought unlikely to seek help from Christian organisations. The JPGAW observed that “the girls have been lured from their parents and natural protectors, to be taken for immoral purposes to lands strange to them where a language they cannot understand is spoken.” According to Tananbaum, “[t]he founders soon learned that local prostitution was only a small part of a worldwide sex slave trade involving a number of Jews and extending from Eastern Europe to South America” and that “[w]hile small in total number, Jews made up a significant proportion of white slavers.”35 “The principal ‘contribution’ made by Jews was the supply of girls to the entrepôts of the system in Buenos Aires, Bombay, Constantinople, and elsewhere, fresh from the East European Pale and London also”, according to Gartner. As Las describes, “Jewish sex traffickers were prominent in major transit points from Europe to Latin America, such as Berlin, London, and Hamburg. In the latter, for example, of 402 sex traffickers caught by police in 1912, 271 were Jewish.”36

Numbers of immigrants

The immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe into Britain and America should be thought of less as a great flight of innocents from persecution and more as a great transposition of a large part of the Jewish population and its ways of life into the receiving countries. The larger the Jewish population in the West grew, the easier it was to avoid adapting or assimilating, even if the setting had changed for some from rural to urban, and some old trades were unviable in the West. The years from 1870 to 1914 “witnessed a phenomenal growth” of the Jewish population “both quantitatively and qualitatively” according to Immanuel Jakobovits. Gartner says that the population movement “was of vast proportions”.37 As Alderman describes,

“On the eve of the Russian pogroms the number of Jews living in London was, as we have seen, about 46,000, and in the country as a whole around 60,000. By 1914 these totals had been dwarfed by the arrival of about 150,000 immigrants; most found their way to London. Merely from a demographic viewpoint this amounted to a revolution. [B]etween 1881 and 1900 London Jewry expanded to approximately 135,000 [and] of these, it was estimated in 1899 that roughly 120,000 were living in the East End.”38

Between 250,000 and 300,000 Jews lived in Britain by the time of the Great War. “Merely from a demographic viewpoint this amounted to a revolution”, says Alderman.39 The inflow also had other revolutionary effects. Assimilation was a threat that was successfully headed off, as Jakobovits describes:

“[T]his influx was no doubt responsible for the intensity of the religious and Zionist commitment, the diversity, and indeed the sheer survival of the community as we know it today. Without this enormous transfusion of new blood, very few descendants of those resident in this country in 1870 would now maintain their Jewish identity, let alone sustain a vibrant Jewish community.”40

Reaction of settled Jews

The position of the older Jewish population was transformed. Through the Jewish Board of Guardians or ad-hoc relief efforts many aimed to help those who had arrived survive and, as seen, avoid being drawn into criminality or slavery, but did not typically encourage more to come. Although, according to Robert Henriques, the influence of the Board of Deputies “had been largely responsible for the liberal immigration policy which had doubled or trebled the numbers of Anglo-Jewry after 1880”41 and, as Gartner says, the “leading families like Rothschild, Montefiore, and Mocatta… would have kept the gates of England always open to all”, they “would give no encouragement and as little aid as possible to immigrants”.42 A typical view was that the “Jewish community could best protect itself from the charge of fostering immigration by ignoring the immigrant.”43 Aid could be expected to beget the demand for more aid. The Jewish Chronicle observed as early as 1880 that “over ninety per cent of our applicants to our Board of Guardians have been subjects of the Czar, and the larger proportion of our poor are invariably immigrants from Russia or Poland.”44 With whatever reluctance, though, aid and other kinds of communal uplift were provided. A typical view at the time was that “[t]hey will drag down, submerge and disgrace our community if we leave them in their present state of neglect”.45 Alderman summarises:

“Jews already settled in Britain objected to foreign-born Jews coming to Britain because these foreign Jews drew attention to themselves, and brought political controversy in their wake, so that the public mind became focused upon Jews as foreigners and a cause for concern at the very time at which the established Jewry was trying its hardest to blend itself, chameleon-like, into its non-Jewish environment… Jews became news.”46

Blending in became impossible, the more so as newcomers brought new ideas and advanced them with vigour and disregard for any pre-existing consensus. The immigrants, unlike the Rothschilds and the cousinhood, were “Poor (for the most part), Yiddish-speaking, Orthodox, socialist and Zionist”.47 As James Appell describes, the immigrants into London also “resented an attitude towards them from their co-religionists which placed low value on the character of the immigrant.”48 There was unanimity on two points, though: “[t]he Yiddish press kept a prudent distance from contentious social and economic questions, except the defence of Jews against anti-Semitism and in favour of free immigration to England.”49 The newcomers outnumbered the older Jewish population manifold, and today “[t]he vast majority of British Jews are third- or fourth-generation descendants of working-class migrants from eastern Europe”, according to Alderman.50 As will be seen in future essays, Britain was altered by the incomers in unprecedented ways. As Alderman says,

“The Jewish immigrants changed the shape of the British polity as surely as they changed the structure of British Jewry: the Jewish experience and the British experience merged and affected each other in a manner far more central than that offered by emancipation itself.”51

That ‘mass immigration’ into Britain began in 1997 or later is a myth convenient to those who condone the smaller numbers that came before. First as immigrants themselves, then as advocates, instigators and facilitators, Jews have been inseparably involved with mass migration into white countries. Their own movement through Europe, sometimes marching in columns, prefigured that of Muslims in the decades since the Second World War. Angela Merkel, who proudly opened Germany to the entry of more than a million Africans and Asians per year from 2015, has been lavishly acclaimed by Jewish activists and the state of Israel. Vaguely the advocates of immigration speak as though her importees were all refugees, a tactic that continues to work. Except in Israel, Jewish organisations, including the Board of Deputies, routinely cite the experiences of their ancestors to justify their pro-immigration stance. While British electors and leaders continue to respond cravenly, they will do nothing for their own nation. Repudiating the myths may help revive it.

Modern British Jewry, Geoffrey Alderman, 1992, p117

The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000, Todd Endelman, 2002, p73-4

Controversy and Crisis, Geoffrey Alderman, 2008, p274

Geoffrey Alderman in Leeds and its Jewish Community, edited by Derek Fraser, 2019, ch1

Endelman, p106

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p63-4

The Jewish Community in British Politics, Geoffrey Alderman, 1983, p31. The sabbath was to become more withstanding when it came to the controversy over Sunday trading laws, to be covered in a later article.

Endelman, p36, 101, 277 (note 36)

Endelman, p79

Controversy, Alderman, p234

Endelman, p106. Endelman adds parenthetically that the Board “continued to make this claim throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although there was no legal basis for it.” For more on the question of the extent to which the Board speaks for Jews, see The Communal Gadfly, Geoffrey Alderman, 2009, p15-28.

See The Rise of Modern Jewish Politics, C.S. Monaco, 2013. Today, similar practices are continued by the likes of the World Jewish Congress and the Anti-Defamation League, though Jews’ situation has been transformed since the 1880s.

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p96

Endelman, p123-4

Jewish Community, Alderman, p37-8 and Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p99. See also Alderman, MBJ, p98-9: “[M]ost British Jews supported Disraeli’s Eastern policy.”

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p98-9

ibid., p99-100

ibid., p99-100

ibid., p99-100]

Endelman, p81. See also p128: “Contrary to popular myth, East European immigration did not begin with the pogroms that swept through Bessarabia and Ukraine in 1881.”

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p112. ‘Pogroms’, referring varyingly to organised riots against Jews or to more spontaneous inter-communal violence, had occurred before 1881, but the term ‘the pogroms’ is sometimes used to refer to the violence of 1881-2 and the subsequent mass emigration.

ibid., p82

The Jewish Immigrant in England, 1870-1914, Lloyd Gartner, 1973, p41

Endelman, p128-9. See also Gartner, p41. As Gartner says of the population increase, “The economic structure of Jewish life failed to expand with the needs imposed by this unprecedented increase.” See Gartner, p21. “Economic backwardness” was a cause of broader trends in rural-to-urban migration at the same time. According to Gartner, “[b]etween the earlier years of the nineteenth century and 1930 occurred the heaviest voluntary migration of people known in history… 62,000,000 persons… crossed international frontiers in this age of relative ‘free trade’ in human movement… migration, even of such dimensions, was itself partly an aspect of such pervasive nineteenth century trends as industrial development, urban growth, and strivings for personal freedom. Under the heading of migration one may well include tens of millions more who crossed no political boundary, yet traversed an economic frontier by pulling up stakes from a farm or village community and settling in an industrial city within their own country.” Gartner, p270

Jewish Immigrants in London, 1880-1939, Susan Tananbaum, 2014, p22

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p111-2. Columns of African and Asian ‘fusgayers’ marched through Europe in 2015.

Gartner, p46-7

Gartner, p12

Russians, Jews and the Pogroms of 1881-2, John Doyle Klier, 2011, p373. In the 1940s, the Jewish-owned Gleaner used similar methods to entice Afro-Caribbeans to move to Britain.

Gartner, p29. He cites the example of a villager seeing the volume of money being sent from Britain to his neighbours and deciding to move too.

White Slavery, Nelly Las, Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, 2021. Jewish Women's Archive

Tananbaum, p19

Gartner, p183. “In 1910, the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women (JAPGW) called a conference in London to discuss the issue. It was attended by representatives from all over the world and focused on Jewish women from Russia and Romania leaving Europe and becoming involved in prostitution in South America. The editors of Anglo-Jewry were concerned that white slaving was seen as a Jewish issue and that more than just Jews were involved in the trafficking of women. At a Yorkshire level, the Hull Jewish community were sufficiently concerned that they monitored all single Jewish girls who came through the port as lone travellers and checked that they safely reached their destination.” Grizzard in Leeds, edited by Fraser, ch7

Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea, Linda Gordon Kuzmack and Ellery Gillian Weil, Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, 2021. Jewish Women's Archive

Tananbaum, p132-3

Las, 2021

Preface by Immanuel Jakobovits to The Jewish Immigrant in England by Gartner, p1, and p45

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p117-8

Controversy, Alderman, p196-7

Jakobovits in Gartner, p1. Endelman concurs with Jakobovits: “[W]ithout this infusion of new blood, the small, increasingly secularized, native-born community, left to itself, would have dwindled into insignificance, as drift, defection, and indifference took their toll.” Endelman p127

Sir Robert Waley Cohen, 1877-1952: A Biography, Robert Henriques, 1966, p353

Gartner, p50-1

ibid., p55-6

ibid., p41]

James Appell in New Directions in Anglo-Jewish History, edited by Geoffrey Alderman, 2010, p31-2

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p120

Alderman in Leeds, edited by Fraser, ch1

Appell in New Directions, edited by Alderman, p31-2

Gartner, p260

Controversy, Alderman, p313

Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p102

This is an extraordinary deep dive into the Jewish history of Britain. Their power being overpowered and esoteric makes tracking them a better way of understanding despotic events throughout our history. Thanks for your time in putting this together.

Great job as always. Important that Jews pursued their interests, not British interests when they achieved power in Britain. Same in America.