Our last article described some of the activities of the Focus and the early stages of their project to supplant British foreign policy with their own: regime change in Germany by threats or by war. Here we examine the collaborative efforts of the Focus and the Soviet Union toward that aim in 1938.

Collective security

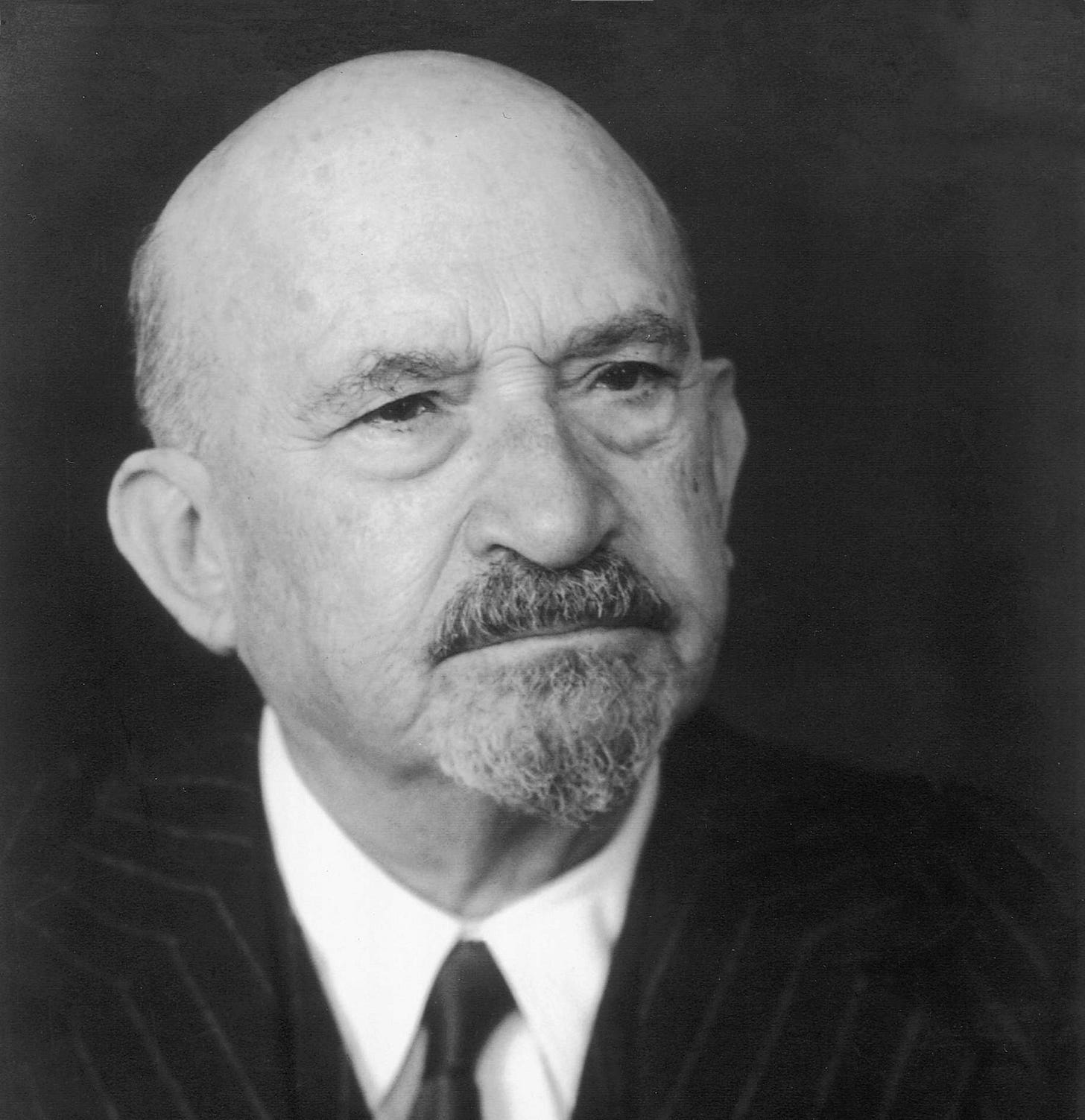

Since the founding of the Focus in 1936, its members and their allies in the Foreign Office sought an alliance between Britain and the Soviet Union and were particularly attracted to Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister. The Conservative MP Robert Boothby wrote in his memoirs that the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, “could have chosen either Russia or Germany as an ally” and that Boothby “preferred the former ‘because socialism was still their proclaimed goal; because in socialism there was at least some hope, and because Litvinov had espoused the cause of collective security’.”1 Litvinov had espoused that cause since December 1933. He argued that the Soviet Union was interested “not only in its own peaceful relations with other states, but in the maintenance of peace generally.” Litvinov persuaded Stalin to let anti-fascism surpass anti-capitalism in urgency in foreign policy, entailing a more particular focus on Hitler’s Germany. The espionage and subversion operations of the NKVD and the Comintern in Britain and around the world continued as before.2

According to Geoffrey Roberts, “Litvinov’s doctrine of the ‘indivisibility of peace’ was underlined by Stalin at the seventeenth party congress in January 1934 when he defended Soviet détente with France on the grounds that ‘if the interests of the USSR demand rapprochement with one country or another which is not interested in disturbing the peace, we adopt this course without hesitation’.”3 The countries not interested in disturbing the peace were the beneficiaries of Versailles and Trianon; the status quo was a partitioning cage for Germany. In any case, peace was an expedient stance for countries building their war capacity. Such were the interests of the USSR, as Richard Overy describes: “Like Germany, Italy and Japan the Soviet Union saw an intimate relationship between domestic economic development and future security, though the Soviet Union was rich enough in resources to be able to develop autarkic policies without foreign expansion.”4

Time was on the side of the already-autarkic, as was France. As Roberts says, “It was partly at France’s behest that the USSR joined the League of Nations – an organization that the Soviets had previously scorned as a ‘capitalist club’ responsible for carving up the globe – in February 1934.”5 The USSR in fact joined the League in September of that year; it did so at the behest of Czechoslovakia and France, allied with one another since 1924. The League, all three perceived, was a potential vehicle for their shared anti-German purposes. The Focus, and Winston Churchill in particular, wore defence of the Covenant of the League as their cloak, though the cloak became ragged after the Soviets disclosed what they meant by collective security to eastern Poland in October 1939.

From the Versailles settlement onwards, as though they had not been victors, French leaders agitated against Germany, and against peace and cooperation in general, at every juncture. Poland, allied with France since 1923, made a declaration of non-aggression with Germany in January 1934. The following month, Poland renewed the non-aggression pact it had made with the Soviet Union in 1932. According to Piotr Wandycz, “The reaction in France” to the declaration with Germany “was distinctly negative,” although it “was, in effect‚ logically included in [the] accords of Locarno.”6 When France ratified its own pact with the Soviets in February 1936, Hitler declared it a violation of the Locarno treaties and reoccupied the Rhineland. Poland’s foreign minister Joszef Beck expressed some sympathy for Germany’s position, understanding the problem of hostile powers to the east and west; the French, encircled by nothing worse than the sea, then “engaged in intrigues to have Beck removed from his position.”7

French politicians and civil servants saw Poland and Romania as pawns in a game against Germany. According to Dov Lungu,

“Romania was important to the French strategically: first, the denial of German access to its oil, in which they had substantial investments and the Germans had few, was considered an important condition for the victory of France and its allies in a protracted European war; second, in such a war, Romania was to be assigned an important role in the defence of Czechoslovakia. The Romanians were expected to free the Czechoslovaks from worrying about their rear by paralyzing the Hungarians and, perhaps, by allowing Soviet military units coming to the assistance of Czechoslovakia to reach that country through Romanian territory.”8

In the latter scenario, France permitted Romanians to hope, or even assume, that the Soviet forces would withdraw after generously rescuing the Czechs. Even then, Romanian governments never fully consented to the role magnanimous France had assigned them. In December 1937, a pro-German government led by Octavian Goga was formed in Romania. Goga’s government began to remove citizenship from much of the Jewish population. As Rebecca Haynes describes, the result was

“to bring the economy to a standstill as Jews boycotted work and withdrew their money from the banks. The Jewish World Congress and the Federation of Jewish Societies of France petitioned the League of Nations to investigate the situation in Romania. The British and French governments subsequently put pressure on Romania to comply with the 1919 Minorities' Protection Treaty under which Romania was obliged to treat her citizens equally regardless of nationality.

The Goga-Cuza government fell from power largely as a result of western displeasure at its antisemitic measures… Without any formal commitment from Germany to guarantee Romania's frontiers, Carol could not afford to alienate his western guarantors. At the same time, the extreme right-wing nature of the Goga-Cuza government had roused the wrath of the Soviet Union [and] the chaos created by the regime's antisemitic legislation… impeded the flow of Romanian agricultural produce and petroleum to the Reich.”9

Czechoslovakia

Edvard Benes, the Czech foreign secretary until December 1935 and president thereafter, personified ‘Czechoslovakism’, and what could be called the Europe of Versailles, along with Tomas Masaryk, the state’s only president before Benes, and Jan Masaryk, Tomas’ son and the ambassador to Britain. Benes was socialist though not Marxist. Czechoslovakia had avoided diplomatic recognition of the Soviets until Franklin Roosevelt, US president from March 1933, began to show favour to them. As Igor Lukes describes:

“The shadow of Hitler, his racist doctrine, and his nationalistic claims gave pause to European democracies and autocracies alike. As a consequence, many countries started paying court to the Kremlin. In November 1933 the United States, that bastion of capitalism, recognized the Soviet Union de jure. From then on, few were willing to be left behind.”10

The Kremlin’s proclaimed policies of collectivisation and dekulakisation had caused the deaths of more than a million of its own citizens in that year alone. Thanks to the preferences of the US president and the World Jewish Congress, the benefit of doing so in ways deemed neither “racist” nor “nationalistic” was immense. Lukes tells us that Benes and his advisers “knew—in rough terms—that Joseph Stalin was extraordinarily brutal”, but they “did not intend to live in the Soviet Union; they only wanted to develop a security arrangement with it.”11 Then as now, leftist and Jewish cant about human rights was often wholly pretextual.

The basis of Benes’ foreign policy was imaginary, as Lukes describes:

“From Prague's perspective, Adolf Hitler made the existence of the Soviet card welcome. … [A]n equilibrium of power in Europe had to be reestablished. It was necessary to compensate for the German threat by bringing Moscow westward and giving it a real presence on the scales of power in Europe. This policy, Benes believed, was… what the traditional concept of balance of power was all about.”12

The notion of the balance of power was not traditional in Britain, let alone elsewhere, and was a pretext invented earlier in the century by Eyre Crowe and other anti-German activists in the British Foreign Office to justify alliances with France and Russia while affecting defensive intentions; retrojection onto previous centuries enabled the advocates of the doctrine to snidely portray their innovation as hallowed.13 Geoffrey Roberts, a sympathiser of the Soviets’ strategy, says that the allegation that it was “a policy of encircling Germany, much as Russia had done before the First World War… was broadly accurate”.14 Crowe himself might not have imagined allying with a communist regime, but somehow the ‘Crowe school’ continued after the Great War; as their efforts conduced toward the Soviets’ interests, they are perhaps better termed the Litvinov school.

For the Czechs, as in Britain’s case, opposition to Germany meant alignment with France. “Benes was encouraged by signs of growing Franco-Soviet cooperation… For its own reasons, Paris was greatly concerned about the reemergence of the German threat…”15 France already posed to Germany the kind of ‘threat’ Churchill ‘warned’ Germany might one day pose to Britain, and had already occupied the Ruhr valley from 1923-25, but its leaders contemplated with dread the prospect of having to parley respectfully with other states one future day. Benes, at any rate, probably chose the side he believed would prevail.

Once Czech relations with the Soviets had been established,

“Benes immediately started using his considerable influence in Geneva to bring about Moscow's admission into the League of Nations. He succeeded on 18 September 1934. With Benes's prompting, the Fifteenth Assembly of the League even went so far as to invite the Soviets to join. In his first speech at the League's assembly, Litvinov recorded ‘with gratitude the initiative taken by the French Government… and the President of the Council, Dr. Benes, in the furtherance of this initiative.’ This was not mere persiflage. Benes wielded real influence in the League, and he used it to help the Soviet case.”16

Benes agreed a treaty with the Soviets in May 1935 (coming into effect after ratification the following March) in which the Czechs included a stipulation that the Soviets would only send forces to assist Czechoslovakia if France did first. Britain and France supported this limitation as it denied the Soviets the freedom to start a war. The Soviets saw it as avoiding an obligation to do so. As Lukes says, “the Kremlin would not want to march on behalf of the bourgeois Czechoslovak government unless France had already absorbed the blows of Hitler's Wehrmacht.” The treaty “strengthened Prague's resolve to resist the Third Reich” rather than “seek a rapprochement with Berlin” which “would have been the worst possible development from the Kremlin's perspective”.17 Happily for the Soviets, the alliance “pushed France to the position of a shield between Germany and the Soviet Union”. In 1938, “France would be able to weasel out of its obligations toward Czechoslovakia only by dishonorably breaking its legal commitment. The Kremlin, on the other hand, would use the stipulation to maintain complete freedom of action throughout the crisis.”18

Absurd as the French position was, it was welcome to those for whom helping the Soviets had become the aim. Churchill and the Soviet ambassador in London, Ivan Maisky had been introduced by Robert Vansittart in 1934 and had been meeting privately ever since. By February 1936, as David Irving describes,

“[t]he peripatetic American diplomat William C. Bullitt, visiting London at this time, was baffled at the mounting hysteria he found: the German ‘menace’, he reported to Washington, was being played for all it was worth. At dinner tables he heard people say that unless Britain did not make war on Germany soon, Hitler would have his way in Central Europe and then attack Russia. ‘Strangely enough,’ wrote Bullitt to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, ‘all the old anti-Bolshevik fanatics like Winston Churchill are trumpeting this Bolshevik thesis and are advocating an entente with the Soviet Union!’”19

Benes declared after making the agreement that “Stalin's Soviet Union was ‘a mighty shield of peace in Europe.’”20 Still, in pursuit of “strengthening Prague’s resolve”, the Soviets saw fit to lie. In June 1935, after signing the pact, Kliment Voroshilov, the Soviet defence secretary, told Benes “We're not afraid of Hitler. If he attacks you, we'll attack him…” When Benes sought verification, “Litvinov assured him that Voroshilov had expressed the opinion of the Soviet government.”21

Stalin was inclined to be less discriminating in regard to ‘capitalist’ powers than was Litvinov. “He restrained Litvinov’s anti-Nazi tendencies somewhat and was receptive to German overtures about an expansion of trade relations” as Roberts says, in order “not to burn all his bridges to Berlin.”22 The aim was not to simply goad Germany into war, at least while Britain and Japan were uncongenial to the USSR, but Stalin intended Czechoslovakia to either inhibit German (and Polish and Hungarian) territorial revisions by its heavily armed presence or to provoke Germany into a war on two or more fronts. Benes was considered useful toward these aims. The Czechoslovak Communist Party was required to drop its revolutionary stance toward the government in accordance with the new policy adopted at the seventh congress of the Comintern. In June 1936, the CPC’s leader Klement Gottwald returned from Moscow with new orders “to help strengthen Czechoslovakia's ability to defend itself against Hitler, thereby erecting a protective shield in front of the Soviet Union.”23

Spring 1938

Even with the ‘help’ of the CPC, the Czechoslovaks’ ability to resist Hitler’s territorial demands diminished sharply when Germany occupied and united with Austria in March 1938. Czech forces were thereafter distributed more sparsely along a greatly lengthened border with Germany. The less viable the Czechoslovak state became, the more the Soviets encouraged intransigence:

“Police informers inside the communist apparat reported that as a result of the Anschluß Moscow reaffirmed its order to abandon the dictatorship of the proletariat [communist revolution] as the CPC's immediate objective. Instead, all of its strength was to be committed against Nazism… [A]fter the destruction of the Third Reich… the dictatorship of the proletariat would be resurrected as the party's main objective. The main task of the CPC was to ensure that the Czechoslovak-German conflict would be fought as an all-out war, whatever the consequences.”24

The day after the German-Austrian union, in collaboration with Litvinov’s man in London, Ivan Maisky, Churchill went public with the suggestion that “the only sensible policy to deal with the obvious German threat to European peace was a ‘Grand Alliance’ of mutual defence based on the Covenant of the League of Nations.”25 Churchill thereafter began to openly call for Britain to support the Soviet Union. His book Arms and the Covenant was released in June 1938; in October that year, he met with the BBC producer and Soviet spy Guy Burgess and gave him a signed copy.

Rather than aggravate the disputes between the European powers, Neville Chamberlain sought to alleviate them by helping Germany get most of what it demanded. Naturally, he did not see the USSR as a partner. According to John Charmley, Chamberlain “saw in Russia a dictatorship as evil as Hitler’s and a country which was ‘stealthily and cunningly pulling all the strings behind the scenes to get us involved in a war with Germany’”.26 Chamberlain thought that a “positive response to Russian requests for talks would be the prelude to war, whilst a guarantee to Czechoslovakia would ‘simply be a pretext’ for that war.” The Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, who was yet to be converted by the warmongers, “reminded the Foreign Policy Committee that the more closely they associated themselves with France and Russia, ‘the more we produced in German minds the impression that we were plotting to encircle Germany and the more difficult it would be to make any real settlement with Germany’.”27

Halifax and Chamberlain identified the raison d’etre of Churchill and the Focus, but as they never renounced British involvement in France’s disputes with Germany, Chamberlain was susceptible to ensnarement in those disputes by the means in which the war party specialised. The private intelligence networks run by Robert Vansittart, Lord Lloyd and others, and the alarming ‘reports’ and rumours they produced, were one such means. Another was direct incitement of hostility between Germany and Czechoslovakia. Lukes identifies Litvinov as the most likely culprit for the false but convincing intelligence reports of German mobilisation near the Czech border which provoked a partial Czechoslovak mobilisation of forces on 20th May 1938.28 All the Soviets’ behaviour is consistent with an intention to provoke a war and avoid committing forces to it for as long as possible. On 11th May, Litvinov had told the Czech diplomat Arnost Heidrich that

“[W]ar was inevitable. We know, he continued, that the ‘West wishes Stalin to destroy Hitler and Hitler to destroy Stalin.’ But Moscow would not oblige its enemies, warned Litvinov. 'This time it will be the Soviets who will stand by until near the end when they will be able to step in and bring about a just and permanent peace.’”

According to Lukes,

“Litvinov's summary… was authentic… Moscow apparently hoped that a collective of states would emerge that would commit itself to an anti-Hitler agenda. The Kremlin intended to strengthen the collective's resolve by its own warlike élan, then drive it into a shooting war with Hitler—and stand aside… Before the crisis, the Kremlin had strengthened Czechoslovakia's determination to defend itself against the Third Reich by posturing as a reliable ally. Once the crisis started, however, Soviet officials retreated and made themselves unavailable for official business..”29

Litvinov believed that time was on the side of the Soviets, “because the future war, originally fueled by nationalism, would have gradually become a revolutionary war against the European bourgeoisie”. Such a war would be “a guarantee against a Franco-British-German rapprochement, which would constitute the greatest threat to Soviet security.”30

War failed to eventuate in May, but the war party exploited what they saw as an opportunity to humiliate Hitler. Reginald Leeper, who used his position as head of the Foreign Office news department to form a cartel of compliant diplomatic correspondents from major newspapers, had recruited Churchill into the Anti-Nazi Council, from which was formed the Focus. As David Irving describes, Leeper openly used Foreign Office press conferences to aggravate Anglo-German relations: “When no tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia, Leeper poured fuel on the flames, flaunting it as a triumph of ‘collective security’ over Hitler’s ambitions…”31 On June 2nd, at a League of Nations demonstration, “[r]eferring to the recent Czech crisis,” Churchill “crowed over Hitler’s apparent climbdown on May 21 - claiming it as a definite success for collective security - and scoffed at the critics of rearmament…”32 Supporters of the League and its Covenant appear to have drifted from their professed pacific origins. Irving continues: “Months later, Hitler would still betray a smouldering bitterness over the episode: despite every assurance… that not one German soldier had been set in motion, Fleet-street had crowed over Germany ‘bowing to British pressure.’”33

Summer 1938

That the reports of German mobilisation were false, and that his Soviet allies had avoided contact during the hour of need, somehow failed to cause Benes to doubt what Voroshilov and Litvinov had previously asserted, that the Soviets would send forces to fight any German invasion. That Romania or Poland sat between the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia and had not agreed to allow Soviet forces to travel through their territories was also unperturbing. The Soviets thus expected their provocative deceptions to bear more fruit. Lukes asks

“What did Litvinov do in June 1938 to clear away the clouds gathering above Czechoslovakia? Did he raise the issue of the corridor with Bucharest? Did he even talk to Benes? He did neither. What Litvinov really wanted was to break through the emerging diplomatic blockade around the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia's fate was of secondary importance.”34

Andrei Zhdanov, a leading Central Committee member trusted by Stalin, told the Czechoslovak Communist Party the real plan in secret in August 1938, his address confirming what the CPC had been told after the 7th Congress of the Comintern in 1935: the Soviets pursued ‘collective security’ as the most likely recipe for war among capitalist states and class war across Europe.35 Why the same was welcomed by anyone else ought to be a central question for historians.

September 1938

Though having never given any guarantee to Czechoslovakia, the consensus among politicians and civil servants for joint action with France caused British entanglement in the Czech dispute with Germany. Britain involved itself to help extricate France from the obligation the latter had undertaken in 1935, i.e. to preserve Britain’s alignment with France while avoiding war.36 This was considered a better option by the vilified ‘appeasers’ than leaping to the assistance of a state which had chosen to side with the Soviets and which Voroshilov laughingly referred to as “a dagger in Germany's back”.37 The so-called ultimatum British and French diplomats issued to Benes after the Munich summit in September 1938 was a statement of non-intervention which helped preserve peace; that Benes and Litvinov were disappointed to receive it would be forgotten had they lacked the support of those who went on to write the victors’ history.

Churchill and other Focus members spent the September crisis making every possible attempt to force Britain and France into war. According to David Irving, with Chamberlain’s approval,

“...the home secretary Sam Hoare placed wiretaps on Eden, Macmillan, and Churchill - all future prime ministers. MI5 was already tapping embassy telephones. Vansittart, wise to the ways of ministers, eschewed the telephone and contacted Winston and Labour conspirators only in their private homes. …Neville Chamberlain betrayed no feelings when Messrs Churchill and Attlee were heard conniving with Maisky and Masaryk, undertaking to overthrow his government; nor when Masaryk telephoned President Roosevelt direct… MI5 has declined to make available the British transcripts… The German intercepts of London embassy communications indicate that Masaryk was furnishing documents and funds to overthrow the British government.”38

After harassing French ministers by phone, Churchill and other members of the Focus flew to Paris to collaborate with the Czech ambassador in Paris, Stefan Osusky, in a plot to simultaneously collapse the British and French governments. Eric Phipps, the British ambassador in Paris, telegraphed to Halifax that “His Majesty’s government should realise [the] extreme danger of even appearing to encourage [the] small, but noisy and corrupt, war group here.” The war group tried to close off any means of peaceful resolution. “General Spears and seven others of the Focus, including Harold Macmillan, sent an urgent letter to Lord Halifax threatening a Tory revolt if the screw was turned on Benes any tighter as Hitler was demanding.”39 They then resorted to an attempt to sabotage Chamberlain’s negotiations with Hitler, as Irving describes: “They decided that Winston should go to Lord Halifax and persuade him to put out a threatening communiqué before Hitler’s broadcast. This would force Chamberlain’s hand…” There would be “a forty-second announcement broadcast in German over Nazi wavelengths in the pause just before Hitler spoke. All Germany would then hear of England’s resolve to fight.” The text “was headed ‘official communiqué’ and typed on foreign office notepaper. Rex Leeper, one of Masaryk’s ‘clients’ at the FO who had steered Britain to the brink in May, sent it to Reuter’s agency. (Afterward the FO and the French foreign ministry immediately disowned it...)” However, according to Churchill’s comrade Frederick Lindemann, the BBC “fumbled or refused to break international wavelength agreements, so it went out only over the conventional channels, an hour after Hitler’s speech.”40

Even after Benes submitted to Hitler’s demands for control of the Sudetenland, as he was jointly advised to do by Britain, France and Italy, Churchill urged Masaryk to “implore Dr Benes to… refuse to pull Czech troops out of the vital fortifications” for as long as possible as, in Churchill’s words, “a tremendous reaction against the betrayal of Czechoslovakia [was] imminent”. Irving refers to this as Churchill’s “final incitement to war - for such there would have been if Benes were now to disregard the Four Power agreement.” Cadogan, Vansittart’s successor as head of the Foreign Office, “recorded in amusement that Winston, Lloyd and others were still ‘intriguing with Masaryk and Maisky.’”41

Amid the crisis, Masaryk was also lobbied by the Focus’ Zionist associates, who awaited such moments of British vulnerability. On 23rd September, as Irving says, “Recalling Churchill’s June 1937 advice to wait until Britain’s hour of distraction, Chaim Weizmann, Israel Moses Sieff, and the other Zionists bore down on Jan Masaryk… urging war.”42 On the 28th September,

“Over at the Carlton Grill… Chaim Weizmann… invited several gentile Zionists to discuss how to exploit the Czech crisis in the context of Palestine. Britain had only two divisions there, and only two more available for France… A year earlier a foreign office memorandum had pointed out that the Zionist policies of the colonial office were rousing anger throughout the Moslem Middle East, and that there was a powerful argument for revising them if the air situation was as perilous as Mr Churchill claimed.”

The colonial secretary, Malcolm Macdonald, warned Weizmann that, “should war now break out, Palestine would be subject to martial law and further immigration halted. Weizmann wrote to him that same day, warning that the British must choose between friendship of Jewry and of Arabs.”43

Weizmann’s audacity in issuing warnings to the British Empire invites more investigation than it has yet received, as does the choice he presented. The friendship of Jewry, an unfortunate people exiled from dozens of realms and oppressed throughout history for no reason, was surely a paltry reward for angering the vastly more numerous Arabs. It also proved an uneven kind of friendship, as Lord Moyne or the inhabitants of the King David Hotel might attest. Still, though the Zionist leaders were inciting war among European nations and blatantly plotting treason against their host country, the smaller, more troublesome group had its way over the succeeding decade. No doubt this owed much to the favour it won among a section of the British upper class, leaders of anglo-Jewry and the members of the Focus. As Martin Gilbert describes, “On 8 June 1937… at a private dinner given by Sir Archibald Sinclair at which Churchill was present, as well as James de Rothschild and several parliamentary supporters of Zionism: Leo Amery, Clement Attlee, Colonel Josiah Wedgwood and Captain Victor Cazalet”, Churchill told Weizmann “‘You know, you are our masters…’ and he added, pointing to those present, ‘If you ask us to fight, we shall fight like tigers.’”44

In September 1938, Zionists were attempting to organise the eviction of British forces from Palestine, if necessary by armed insurrection. On October 1st, “...as Masaryk walked into Weizmann’s home,” he encountered the same crew “discussing ways of destroying Chamberlain’s policies on Palestine”. Having been informed that war with Germany would entail conscription of Jews in Palestine, Blanche Dugdale, niece of Arthur Balfour and a leading gentile Zionist, wrote that “We can only work by every means, fair and foul… to buy land, bring in men, get arms.’”45 Zionists have always attacked any suggestion that their loyalty to their host countries were compromised, but, regardless of ancestry, those who seek opportunities in a nation’s vulnerabilities can fairly be counted among its enemies, as can those, like Churchill, who advise and encourage them to do so.

Lord Lloyd

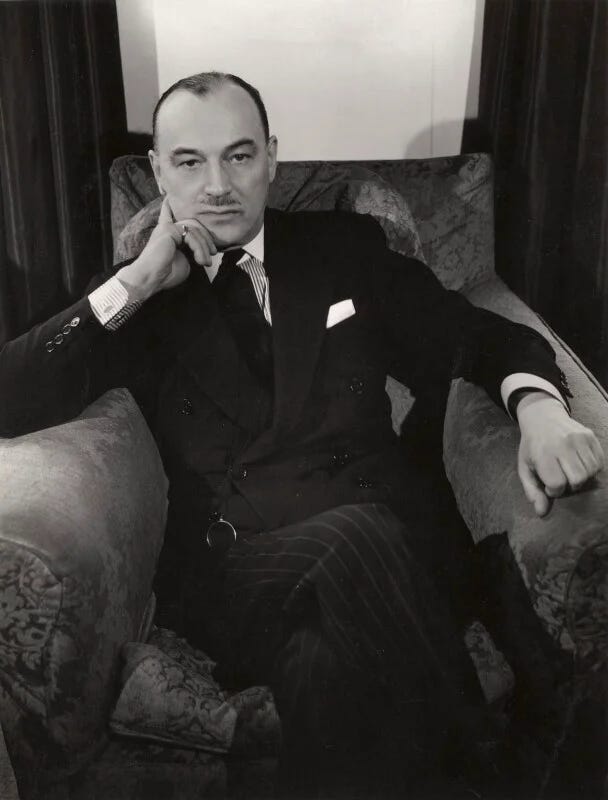

Though under Chamberlain they made slower progress, the Zionists had only to wait for him to be replaced, to which end their friends in the Focus worked ever more energetically. They leveraged personal connections and old friendships and employed pathos and emotive moralising. They redefined words expediently. According to Lord Lloyd, head of the British Council, writing to his friend Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, in September 1938, “If Germany was allowed to annex the Sudetenland not only would Czechoslovakia be at her mercy, but all the smaller European states would draw the conclusion that there was no way of standing up to Hitler and ‘you will have opened a path for Germany to the Black Sea’.” As in the case of Romania’s oil supplies, the need to prevent Germany accessing what the Soviets already had was treated as self-explanatory. Lloyd invoked courage, “sacrifice”, “what is Right” and “to be the champions of weak peoples”, the last of which was “a task surely set us by Providence”. He informed Halifax that “There are worse issues even than war”, referring to peace.46

We may never know how much, if at all, Halifax was swayed by the pretentious use of capital letters, but evidently Lloyd wielded piety as a bludgeon; all talk of concern for “weak peoples” was a veil or a lever to be worn or pulled as was found judicious. The Zionists with whom Lloyd frequently dined, who colluded in the same belligerent cause as he, were explicit about their intention to subjugate or displace the natives of Palestine. We find no objection from Lloyd to Churchill for his ardent support for that project or the forthrightly racial supremacist reasons Churchill gave. Nor did Lloyd write letters pleading the case of the minorities forced to live under the Czechoslovak state since 1919 or, indeed, of the Czechs themselves before that date. We might hope that Providence later reviewed how best to set its tasks, so considerate had it been in the 1930s to Zionists, communists, financiers and manufacturers, and so neglectful to Lloyd and Churchill’s proclaimed interest, the British Empire, and to the tranquility of ordinary European folk.

To suggest that Benes’ government was worthy of the help of Britain would obviously be absurd, but arguably it was not even worthy of that of France. The case for such help relied entirely on the fear campaign against Germany and the apologies, from the same parties, for the Soviet Union. The notion that a helpless ‘democracy’ was being ‘fed’ to a dictator in 1938 was false, as Lukes describes: “By the spring of 1938, the Czechoslovak parliament, the prime minister and the cabinet had been pushed aside by Benes. During the dramatic summer months he was – for better, or worse – the sole decisionmaker in the country.”47 Real democracy militates against the gathering of such autocratic powers even in times of crisis. Czechoslovakia had the kind of democracy any multicultural, civically-defined state should expect.

After Germany successfully “championed” the Sudeten Germans and the Slovaks, Lloyd wrote to the Daily Telegraph that “it was ‘impossible to speak without shame and difficult to speak without indignation, of what we have done to the Czech people’. Disraeli had credited Britain with two great assets, her Fleet and her good name: ‘Today we must console ourselves that we still have our Fleet.’”48 Her Fleet was a great asset, but Disraeli had brandished it in 1877 to prolong the sanguinary Turkish occupation of Christian lands and Churchill used it to starve Germany in 1919; the malnourished state of the German delegation at Versailles detracted from Britain’s “good name”, and Churchill’s. The disgrace Disraeli and his admirers had incurred on Britain’s behalf was mitigated, not extended, when Chamberlain helped extricate France from an alliance it should never have made and on which Benes was a fool to rely.

When the Prime Minister reminded Lloyd in October 1938 that “the policy I am pursuing is a dual one” and that “conciliation is a part of it fully as essential as rearmament”, Charmley says that “Lloyd increasingly felt that what was needed was ‘an alternative National Government’”.49 To form that alternative was the primary objective of the Focus, which Churchill referred to as the “Cave of Adullam” and from which had come one attempt already in April 1938.50 During the Sudeten hysteria, “[f]resh in funds, the Focus began printing millions of leaflets and booked a London hall for a protest meeting… to throw out the Chamberlain four and set up a national government.”51 A new government was needed specifically to collaborate with the USSR.

Exclusion of the Soviets

While Churchill was inciting war in Paris in September, Robert Boothby travelled to meet Litvinov in Geneva and returned saying that “the Russians will give us full support”.52 This was even less true to Britain than it was to Czechoslovakia. Until near the end of the crisis, Benes “was convinced that… the Soviet Union would ‘fight its way through Poland and Romania’ to help Czechoslovakia…”, though the Soviets lacked agreements with either country to do so.53 When asked to confirm the Soviets’ intention to honour the treaty with Czechoslovakia, Litvinov “carefully waited for Benes to surrender before he said publicly that Moscow had given an affirmative answer.” At any rate, because France “had already made clear that it was not prepared to live up to its obligations, Moscow's promises of support had purely cosmetic value.” As Lukes says, after ‘Munich’, ”the Kremlin was able to create the appearance of being supportive of the Prague government but without accepting any responsibility.”54 In 1947, Benes said that “The truth is that the Soviets did not want to help us,” and that they “acted deceitfully.” During the crisis, referring to Sergei Aleksandrovsky, the Soviet ambassador in Prague, Benes said “I asked him three questions, whether the Soviets would help us, and I repeated them. He did not answer, he never answered. That was the main reason why I capitulated.”55 The Soviets appear to have had a reserve plan but their agents failed to activate it. After the war, Klement Gottwald, the Czech Communist Party leader, told Benes “that Soviet leaders had severely criticized [Gottwald] for his failure to carry out a communist coup d'état in Prague during the September 1938 crisis."56

According to Lukes, the Soviets’ desire, short of war, was “a seat at the international conference that would eventually deal with the crisis.” Litvinov told Lord De La Warr, the British ambassador to the League of Nations, “that Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union should meet in Paris to discuss the crisis”; he wanted to avoid an international conference excluding the Soviet Union.57 At Munich, Litvinov’s fear, a “modus vivendi between the Franco-British bloc and the Hitler-Mussolini tandem” which “increased the Kremlin's isolation” was fulfilled.58 Thus “[t]wo days after the conference, Georgi Dimitrov, the Comintern chief, expressed the opinion that the Munich Agreement, was directed against the Soviet Union. He said nothing of Czechoslovakia.”59

Size of forces

Denied war in September 1938, Lord Lloyd and others of the Focus fomented the myth of the ‘betrayal’ at Munich, their equivalent of the ‘stab in the back’ in Germany at the end of the Great War. They put only one of the Czechs’ faithless allies on trial and called the other as a witness. Whereas Benes admitted his mistake eventually, Stalin’s good faith is still argued seriously by some Western historians, lest either the benevolence or the acuity of his allies in Britain, and the regime begotten by them, be doubted.

Most criers of betrayal mean, but say more indirectly, what Frank McDonough brassily asserts: September 1938 was “a lost opportunity to start a two-front war”.60 McDonough also demolishes the fear campaign, carried out since 1933, on which relies the notion of Churchill as a prescient seer of danger. Churchill’s claims had always contradicted the calculations of the disinterested Air Ministry, as intended by Robert Vansittart, who contributed numbers based on ‘intelligence’ from a network composed largely of communists and “Jewish emigrés”.61 According to McDonough,

“The forces available to Germany in 1938 were never as favourable as British ministers, supported by their bungling military and intelligence advisers, had predicted… Hitler’s ability to talk a good fight spread the alarm, but he had been bluffing all along… The French air force outnumbered the Luftwaffe by a ratio of four to three, and those figures excluded additional air force support of Britain and Czechoslovakia… The Luftwaffe’s capacity to bomb British cities was merely a figment of the British Chiefs of Staff’s imagination. No serious German study of the Luftwaffe fighting strength in 1938 has unearthed any plans to bomb Britain whatsoever… the British and French government leaders and their Chiefs of Staff totally misread how much the balance of power was loaded in their favour in 1938.”62

McDonough is unusual among anti-fascist historians in alluding to Germans’ need to consider all the countries surrounding them and implicitly acknowledging that Germany would be insane to launch its whole air force at any of them at once. Even then, McDonough omits to mention the scale of the Soviet forces. According to Manfred Jonas, France, already ahead of Germany in aircraft in September 1938, “began to re-arm in earnest” the following spring and ordered a further 1,000 planes from the USA to be delivered in July 1939. Geoffrey Roberts informs us that “The 1938 Soviet war plan identified Germany as the chief enemy and allocated 140 divisions and 10,000 tanks to the defence of the USSR’s western borders.” Jonas dates the beginning of the Soviets’ rearmament to March 1939.63 To be autarkic and have 140 divisions and 10,000 tanks on one front before even “beginning” to re-arm was a favourable situation indeed; the common idea of the Soviets as ‘defensive’ is more convenient than true. According to Joachim Hoffman, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22nd, 1941,

“the Red Army possessed no less than 24,000 tanks, including 1,861 type T-34 tanks (a medium tank, perhaps the most effective armored weapon of the entire war) and KV (Klim Voroshilov) tanks (a series of heavy tanks), which had no equal anywhere in the world.”

Germany had 3,550 German tanks and assault guns, of which half were light tanks. Hoffman adds that “Since 1938, the Air Forces of the Red Army had received a total of 23,245 military aircraft, including 3,719 aircraft of the latest design.” The lowest Soviet estimates grant that at least 10,000 were ready at the start of Barbarossa to engage the “2,500 combat-ready German aircraft”.64 The aggressive positioning of these forces near the German borders in 1941 was a factor in the vastness of the Soviets’ losses in the early stages of the German invasion.65

Soviet expansion

Geoffrey Roberts describes ‘Munich’ as “a mortal blow to the policy of collective security” which “all but ended Soviet hopes for an alliance with Britain and France against Hitler.” It only ended those hopes temporarily while delivering the Soviets undeserved legitimation in Britain. Roberts says that “Moscow did not retreat into complete isolation. Instead, Stalin bided his time and awaited events.”66

Having never really believed in the Covenant or “the indivisibility of peace”, Stalin was free to sign a non-aggression pact with Hitler in August 1939 which freed Germany to invade France, though presumably Stalin would have preferred a costly, lengthy struggle there.67 Once France was defeated, the Soviets disposed of old, inhibitory pretences and began to issue demands to the “weak peoples” Lloyd assumed they would respect. Between November 1939 and June 1940, the Soviets invaded Finland and annexed Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. They then occupied Bessarabia and northern Bukovina in June 1940; the ensuing mass deportations and killings proved less controversial, both with the likes of Lloyd, who had personally intervened to prevent Romania drawing closer to Germany, and with the World Jewish Congress. Perhaps the specific provisions of the Minorities Treaty were all-important and communist mass murder fell outside its jurisdiction merely by misfortune, or perhaps the leaders of the WJC, like Samuel Untermyer, were obsessively opposed to Hitler and supported the Soviets regardless of the human cost. Certainly Soviet occupation, a nightmare for ordinary Europeans, was welcomed in some circles; as Sean McMeekin describes, when the Soviets occupied eastern Poland in October 1939, "many Jews rejoiced in the news that the red army had arrived".68 The pact with ‘the Nazis’ and the devourment of neighbouring countries apparently only cost the Soviets the support of a few Western fellow-travellers; Churchill remained an eager suitor.69

As we know that Churchill asked for the suppression of accurate force comparisons from the Air Ministry, it is unlikely that sincere dread of Germany was his primary motive in collaborating with foreign governments against his own after 1933. I find no evidence that he became sympathetic to Marxism or was any kind of Soviet agent. Though he was given money by various Jews throughout his life, there was never an evident quid pro quo. Most likely, Churchill and his benefactors understood him to be their advocate and servant in politics, as individuals and as Jews; he did what he could for them. Churchill acted upon what Disraeli presented as an observation: “The Lord deals with the nations as the nations deal with the Jews.” As the interests of communists and “Jewish emigrés” like Jurgen Kuczynski were the same in regard to Hitler’s Germany as those of rich Jewish industrialists like Henry Strakosch and of Robert Waley Cohen, the Board of Deputies and the other “leaders of anglo-Jewry” who secretly financed the Focus, along with Samuel Untermyer’s boycott movement (with which Churchill began his campaign against Hitler in tandem) and the World Jewish Congress, Churchill collaborated with and served all at once, continuing naturally from his earlier life, when Ernest Cassel had been his munificent benefactor (as he was of King Edward VII), and from that of his father, for whom Nathan Rothschild was the equivalent of Cassel, as Nathan’s father Lionel had been for Benjamin Disraeli. As all those interests also coincided with those of the Soviet Union, as expressed through its Jewish diplomats Maxim Litvinov and Ivan Maisky, Churchill naturally served as a voluntary advocate of the Soviet cause, affecting to be concerned with security rather than openly working to replace the existing British policy with one designed to enhance the power of the small foreign minority he regarded as a superior race.70 The Soviets took the position that was natural for the Soviets; so did the Focus, and woe to the ‘cowards’, ‘appeasers’ and ‘fascists’ who tried to take the natural British position.

Weak peoples

Of all the “weak peoples” seeking “champions”, Jews in Britain were the most generously treated by “Providence”. The Czechs and Slovaks, like the Poles and Romanians, were less fortunate. When Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Red Army in 1945 and Benes’ government, then including Gottwald’s communists, subsequently expelled its entire German population, Western reactions were markedly different from those of Churchill and his cohorts in March 1939 when Germany had subjected the remainder of Czechia to protectorate status.71 Gerhard Weinberg adds that

“In 1945, the Soviet Union annexed the easternmost portion of pre-Munich Czechoslovakia on the grounds that the people living there were akin to those in the adjacent Ukrainian SSR – the same basis on which Germany annexed what had come to be called the Sudetenland. In 1968, the army of the Soviet Union, together with units from the German Democratic Republic, Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria, occupied the remainder of Czechoslovakia. No public demand was voiced anywhere then, and to my knowledge no historian has suggested since, that the United States, Britain, France, or anyone else go to war to protect the independence of Czechoslovakia.”72

Within weeks of taking power in 1948, the communist regime of Czechoslovakia, with the Soviets’ approval, supplied crucial arms to Israel, which immediately expanded its territory and drove masses of Palestinians into flight. They and their descendants remain stateless refugees. Churchill smiled to see the “higher grade race” triumph over the “lower manifestation”.

‘Munich’ is said by its detractors to have sanctioned the ‘dismemberment’ of Czechoslovakia. Within three years of independence from the Soviet Union, Czech and Slovak politicians dismembered their conjoined state and have since lived peacefully as two distinct peoples. The Masaryk-Benes era was little less artificial than that of communist rule; the fidelity of the likes of Churchill and Lloyd to Czechoslovakia was no realer than Stalin or Litvinov’s. ‘Munich’ is not a metonym for betrayal of the weak but an object lesson in the warmongers’ craft: they disparage peace and lie about the past to justify their crimes forever after.

Chamberlain and the Lost Peace, John Charmley, 1989, chapter 6

The Comintern adopted the ‘popular front’ policy at its 7th congress in August 1935, a change of approach to the same ends as before. See Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler, Igor Lukes, 1996, page 72

Geoffrey Roberts in The Origins of the Second World War, edited by Frank McDonough, 2011, page 411

Richard Overy in McDonough (ed.), p493

Roberts in McDonough, p412

Piotr Wandycz in McDonough (ed.), p382-3

Wandycz in McDonough, p384. “Warsaw had no cause to regret the demise of Locarno. In fact it meant for Beck the possibility of restoring the Franco-Polish alliance to its original and firm mutual engagement. This may have been wishful thinking, for the Maginot Line and the law of 1935 (defence of homeland and empire) made it clear that France would fight only a defensive war – its military aid to Poland would be of highly dubious character.”

The French and British Attitudes towards the Goga-Cuza Government in Romania, December 1937-February 1938, Dov Lungu, Canadian Slavonic Papers, Volume 30, Number 3, September 1988, p326

Romanian Policy Towards Germany, 1936-40, Rebecca Haynes, 2016, p46. The “Jewish World Congress” presumably refers to the World Jewish Congress. Even if the Treaty was worded to condemn the removal of citizenship but permit collectivisation, arbitrary imprisonment, slavery, torture and summary execution, genuine humanitarians would not have stopped at lobbying Romania alone.

Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler, Igor Lukes, 1996, p35-6. Lukes’ approval is clear: “There seemed every reason to try to bring the Soviet Union into the equation of power in Central Europe; the Third Reich worried all clear-headed observers.” p39

Lukes, p38. According to Lukes, Benes “was a lifelong socialist” for whom “égalité and fraternité were the two most important attributes of humanity. Liberté was secondary… Benes had little trouble accepting the social component of the Bolshevik ideology as he understood it.” p13-4

Lukes, p38-9

Arthur Nicolson, Charles Hardinge and others promoted by Edward VII supported and furthered Crowe’s thinking, helping to cause the First World War. Robert Vansittart was one of the younger generation who continued the theme.

Roberts in McDonough, p413

Lukes, p37

Lukes, p39. My emphasis.

Lukes, p49. “It would become Benes's policy to deal with Moscow via Paris.” p38-9

Lukes, p47-9

Irving, p54-5

Lukes, p50

Lukes, p54

Roberts in McDonough, p413

Lukes, p77

Lukes, p142. According to William West, Czech arms manufacturers, via the Comintern, supplied Austrian communists with weaponry to assist in an attempted revolution in 1934. “This traffic was also a factor in the Spanish Civil War” and “appears to have been organised by Max K. Adler.” Truth Betrayed, W J West, p77, footnote 24

McDonough, p192

Chamberlain, Charmley, chapter 7

Chamberlain, Charmley, chapter 7

Lukes, p148-157, especially p154. Irving speculates that the war party provoked the May crisis or co-ordinated it with Litvinov: “What was the origin of the canard? Did Masaryk talk with Churchill in those crucial days? The ebullient Czech was certainly spotted the day before the crisis in conclave with Vansittart.” Irving, p123

Lukes, p154. “Paradoxically, after the tensions declined, Moscow emerged to claim that the partial mobilization was a success, at least in part because of the firmness of Soviet foreign policy.”

Lukes, p157

Irving, p123

Irving, p127

Irving, p123

Lukes, p193. “To Benes, the Soviet Union wanted to appear ready—indeed, eager—to go to war. Toward the West the Soviet Union needed to present itself as a reliable, strong, but prudent partner. On this front, the main objective was to prevent the Soviet Union's isolation by working against a rapprochement between Western democracies and Hitler.”

Lukes, p191, 198-200. At the Zhdanov meeting with the CPC, Harry Pollitt, head of the CPGB and collaborator with the Board of Deputies and the Home Secretary in terrorism against the anti-war British Union of Fascists, was in attendance.

Considering the enormity of its consequences, historians are remarkably incurious about who ensured the continuation of the Anglo-French entente through the 1920s and 1930s and why.

Lukes, p192

Irving, p138

Irving, p147

Irving, p150

Irving, p156

Irving, p145

Irving, p152

Churchill and the Jews, Martin Gilbert, chapter 11

Irving, p156-7

Lord Lloyd and the decline of the British Empire, John Charmley, 1987, p218-9

The Munich Crisis, 1938, edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, 1999, p15

Lloyd, Charmley, p215, p220

Lloyd, Charmley, p221

Irving, p119. “[T]he New Statesman’s editor put out secret feelers to influential Liberal and Labour politicians: would they join a putative Churchill coalition with Eden as foreign secretary, if their minority parties were strongly represented in his cabinet? It was their first sniff of power for some time. Attlee agreed in principle, but retired into his shell soon after the editor sounded him. Greenwood and Morrison showed more interest, and Bevin was also rumoured to be willing, if offered the ministry of labour. These remarkable soundings, described by Kingsley Martin to Hugh Dalton a few days later, were an echo of things to come.”

Irving, p148

Irving, p142-4

Lukes, p231

Lukes, p229

Lukes, p257. Benes revealed his fury at Stalin’s perfidy on several occasions in 1945. See Munich, Lukes and Goldstein (eds), p20-1

Lukes, p231. It appears to be standard practice among anti-fascist historians to simply ignore this evidence and treat the Soviets, especially Litvinov, as having sagely foreseen the ‘Nazi threat’ and as eager friends of democracy foolishly spurned by ‘the appeasers’.

Lukes, p229

Stalin and Benes at the End of September 1938: New Evidence from the Prague Archives, Igor Lukes, Slavic Review, Volume 52, Number 1, Spring 1993, p48

Lukes, p258. Likewise, “Litvinov's suggestion… did not mention the participation of Czechoslovakia.” Lukes, p230

McDonough, p197

Churchill’s Man of Mystery - Desmond Morton and the World of Intelligence, Gill Bennett, 2007, chapter 9. Vansittart and Churchill tried to silence the Air Ministry rather than prove the accuracy of their estimates.

McDonough, p197-8. Bluffs by Hitler, as when he privately boasted of outmatching the RAF in 1935, had been presented in Parliament and the press as ‘intelligence’ from ‘credible sources’, as had the claims, sometimes humorous, of communists like Jurgen Kuczynski.

Manfred Jonas in McDonough, p409, 440

Stalin’s War of Extermination, Joachim Hoffman, 2001, p30-32

Stalin’s War, Sean McMeekin, 2021, chapter 17. “The Lvov/Lemberg salient… contained the best-armed and most mechanized divisions in the entire Red Army… its fate in the early days of Barbarossa exposed… the baleful consequences of Stalin’s grasping at territory in 1939 and the Red Army’s offensive deployment in 1941.”

Roberts in McDonough, p414. Lukes says that “The Munich affair proved to be a godsend… for the Communist party of Czechoslovakia. Klement Gottwald noted in late December 1938… that, despite its defeat, the CPC had succeeded in drilling into the minds of Czechoslovak citizens the link between the security of their country and the security of the Soviet Union. During the crisis, Gottwald observed, anticommunism had for the first time become unfashionable and unpatriotic. Party propaganda had managed to form the public view that hostility toward the CPC meant endangering Czechoslovakia's national security and that hostility toward the Soviet Union weakened Czechoslovakia.” This paid dividends between 1945-8, after which public opinion was given less regard.

After the start of war between Germany and Britain and France, Czech communists visited Moscow. “The delegation was received by an official of the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was justified, he said: ‘If the USSR had concluded a treaty with the Western powers, Germany would never have unleashed a war from which will develop world revolution which we have been preparing for a long time… A surrounded Germany would never have entered into war… We cannot afford Germany to lose… The present war must last as long as we want… Keep calm because never was the time more favorable for our interests than at present.’ The long-term Soviet strategy outlined… was in harmony not only with the 7th Congress but also with the ideas laid down by Zhdanov in his August 1938 speech before the Czechoslovak Communist party's Central Committee.” Lukes, p258

McMeekin, chapter 6

That is, Churchill continued throughout the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact to court Stalin, who had chosen to ally with Churchill’s sworn enemy, and historians attribute even that to necessity.

“[T]hroughout the years up to Munich [LItvinov’s] was the sole hand in charge of Soviet foreign policy.” The key ambassadors were “Jakob Suritz in Paris, Ivan Maisky in London, Boris Shtein in Rome.” See How War Came, Donald Watt, 1989, p112. Litvinov was succeeded by Vyacheslav Molotov in May 1939 and became the Soviet ambassador in Washington a month before the attack on Pearl Harbour.

“It was with a degree of pride that Andrei Zhdanov, in the autumn of 1947, reviewed the changes World War II brought about in Europe. He noted that the war had significantly altered the international balance of power in favour of the Soviet Union. ‘The war dealt capitalism a heavy blow’, Zhdanov asserted. Some of the main bastions of imperialism were defeated (Germany, Japan and Italy) and others were weakened (Great Britain and France). By contrast, the Soviet Union was greatly strengthened.” Munich, Lukes and Goldstein, p41. Lukes adds that the Soviet position in Europe relied on terror and the goodwill of the USA.

Munich, Lukes and Goldstein, p1

Excellent work. I find the role of Czechs, as one myself, in all this regrettable. To this day, Masaryk and Beneš are considered heroes in the mainstream. Just one small correction at the end, there was actually a vote about dissolution of Czechoslovakia. People voted against it and then it happened regardless as it usually goes in democracies.

Fantastic