The Engine of Compulsory Conformity

The BBC, the Bloomsbury Group, the Comintern and the NKVD in the 1930s

After its first five years in operation, the British Broadcasting Company became the wholly state-controlled British Broadcasting Corporation in 1927. John Reith, the first chief executive, wrote in 1924 of his “high conception of the inherent possibilities of the service” and later asserted that “‘the brute force of monopoly’ was a necessity in British broadcasting.”1 As a preponderance of politicians and civil servants as well as the Newspaper Proprietors’ Association agreed, the grant of the BBC’s first Royal Charter in 1927 and Reith’s ascent to the position of Director-General were virtually unchallenged. The brute force would fare better than the higher conception.

The Company, originally a cartel of radio set manufacturers, had been lucrative for its directors, but the Post Office had sanctioned their privileges for questionable reasons, and after the agreed period of royalties and having established the state enforcement of the licence fee, and under a government less obliging to Marconi and GEC, the Company was reformed into a ‘public corporation’. Reith himself was the leading advocate of the novel concept which, as with David Sarnoff and RCA in the USA, happened to provide him with a personal fief of immense influence. Reith’s “higher conception” consisted in a belief in “democratic aim, not in democratic method”, not aiming to give the public what they wanted, and still less any choice, but rather what he thought best for them.2 The BBC licence fee, originally a device to compel listeners to deliver royalties to the manufacturers’ cartel, served after the BBC’s incorporation to compel them to fund the state broadcaster while all other would-be broadcasters were prohibited.

The Public Corporation

The BBC’s official history describes Reith as desiring an organisation “independent” of the market and of governments.3 This has only ever been the case in the formal sense that the corporation depends directly on the crown instead, but the powers of the crown have for centuries been exercised by the government anyway. As Tom Mills describes, “renewals of the Royal Charter, as well as the appointment of BBC governors and trustees, have formally been made by an Order of the Privy Council” using “the residential powers of the absolutist state which have never been subject to democratic controls” and which are, “in essence, absolutist decrees of the central government, signed-off by the monarch of the day.”4 The government also grants the corporation its licence fee increases.5 The BBC could be deprived of funding or closed by any government that wished to do so, but none ever has; the idea of public corporations were initially embraced by leftists, but the Conservative Party exists to consolidate the gains of their faux-opponents.6

Reith’s BBC consciously strove to present itself as a kind of conglomerated person with whom the public would identify and whom they would trust. In Asa Briggs’ words, early BBC staff wanted “to ensure that people felt—without thinking—that the BBC was theirs.”7 Announcers were soon, by some listeners, "thought of as the BBC, for it was they who mediated between the listeners and the programmes."8 Announcers were deemed the best placed of all BBC employees “to build up in the public mind a sense of the BBC's collective personality.” They would represent “[t]he BBC itself” and its own “policy and ideals”.9 An article in the Spectator in 1936 said that “The BBC has a personality of its own, pervasive and unmistakable, and it affects its reactions to public events, to education, to entertainment, and to the arts: it is the foundation of its policy."10 The Corporation was and is, as with any media organisation, unavoidably biased in whom it recruits, what its editors select to report and omit and how it allocates programme time, but developed the ability to appear objective to many viewers while expressing approval or disapproval by the variation of announcers’, presenters’ and newsreaders’ tones of voice and, in documentaries, the use of background music and lighting.11 The more trusting or unthinking elements of the public are subliminally persuaded by such methods.

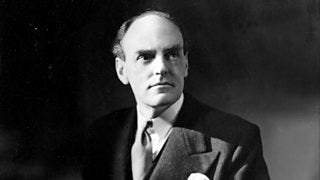

Reith was chosen by the BBC’s first board of directors, but as they receded in importance, he grew, and standard histories of the corporation speak of ‘Reithianism’ as its founding ideology. This blurs the reality, but Reith was certainly a formative factor. He was a Presbyterian who served in and supported the Great War.12 His diary and memoirs show that he opposed unionisation at the BBC and in his previous job, had “no particular feelings about Communism”, privately sympathised with Adolf Hitler at times and made occasional favourable remarks about Benito Mussolini, yet in 1939 described himself as a “Gladstonian liberal”.13 He wrote in October 1942 that Winston Churchill was a “bloody swine” and “the greatest menace we’ve ever had” with “country and Empire sacrificed to his megalomania, to his monstrous obstinacy and wrongheadedness.”14 His insistence on formality, elocution and a privileged position for Christianity are commonly said to characterise the BBC during and long after his tenure, but his own political and cultural views do not appear to have become those of the organisation.

Crusading

Reith appears to have concerned himself primarily with broadcasting per se; to control all the BBC’s output he did not attempt, and those he began to disagree with in the 1930s he had also hired and come to rely upon. As Asa Briggs says, “The BBC’s philosophy owed an immense amount to one man: the BBC’s programmes were the work of many men of extremely varied experience and outlook.”15 He describes them as “men and women who ‘believed in broadcasting’ almost as a social and cultural crusade.”16 They also, more or less frankly, saw broadcasting as a means of indoctrination and intended to use it as such. As early as 1925, the leading Fabian Beatrice Webb had written that wireless had “a stupendous influence… over the lives of the people” and “might become… a terrible engine of compulsory conformity… in opinion and culture” but asserted that the BBC’s use of its influence was “eminently right”. Hilda Matheson, after six years at the Corporation, wrote in 1933 that “Broadcasting is a huge agency of standardization, the most powerful the world has ever seen.”17 Labour politician Herbert Morrison, later Home Secretary under Winston Churchill, had from the BBC’s earliest days “demanded that broadcasting… should be publicly owned and controlled.”18 In 1946, Morrison described broadcasting as “at least as powerful a vehicle of ideas as the printing press” and acknowledged that “the body which decides what goes into a broadcasting programme has an enormous power for good and evil over the minds of the nation” and averred that “that power must not fall into the wrong hands”, out of the right ones.19

After it began to be allowed to broadcast ‘controversial’ programmes from 1927, and as it became involved in education, nearly all the department heads and editors Reith’s BBC hired ensured that the political and cultural output was routinely leftist.20 An early producer of ‘controversial’ programming, Lionel Fielden, wrote that “[w]e really believed that broadcasting could revolutionize human opinion.”21 Charles Siepmann, the second Head of Talks, was in his own words “fanatically devoted”; he believed that

“broadcasting was the greatest miracle in human history… everything that any man had ever written down on paper, every note of music that had ever been composed was now universally available. This was what you might call ‘the new age of cultural communism’. And I believed that.”

Siepmann referred to his own “progressive outlook” and “the progressive policies that both Hilda and I were pushing very hard indeed”. He lamented that Reith agonised too earnestly over balance and didn’t share Siepmann’s “very, very sensitive social conscience”. Siepmann remarked that his own “sense of balance” was “to redress the ultra-conservatism of the culture of that time… my theory of balance 'was subversive in the sense that it was disruptive of the old Conservative clique” and the “Conservative Mind”.22

BBC Education and Talks

The BBC founded several publications, of which Radio Times continues today. Its first and formative editor from 1927 was Eric Maschwitz, son of a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania, whose career, like many BBC employees, included spells in broadcasting, the movie and music industries, the intelligence services, and wartime sabotage and terrorism under the Special Operations Executive. The Listener, founded in 1929, was an “educational periodical”, a printer of BBC Talks and a vehicle for the Corporation’s ‘cultural mission’. “By 1935 its circulation had reached 52,000, more than that of the New Statesman and the Spectator combined.”23 Richard Lambert was the first editor, having previously been, with Siepmann, the BBC’s representative on the Council for Adult Education, which the BBC funded to promote socialists including G D H Cole, John Sankey, William Temple and Harold Laski.24 Lambert employed Janet Adam Smith, later of the Fabian New Statesman, and the homosexual Joe Ackerley as assistant editors; his team’s use of The Listener to promote homosexual and communist poets like Cecil Day-Lewis, Wystan Auden, John Lehmann, Stephen Spender and Herbert Read provoked complaints from readers.25 Christopher Isherwood, another favourite poet, was a close associate of the Berlin-based pro-transgender, anti-nationalist activist Magnus Hirschfeld.26

Talks were originally a sub-division of BBC Education (which also included religion and early news operations), but “...in January 1927 the Control Board decided that a separate “Talks Section’ should be formed, quite distinct from education, news, and religion, with Miss Matheson in charge. She remained there until January 1932, leaving a very powerful imprint on the BBC.”27 Matheson was hired personally by Reith, first as an assistant in Education, then as the first Director of Talks in 1927. The BBC’s news operations began at the same time, initially merely repeating press agency reports. According to Kate Murphy, Matheson was “part of London’s cultural and intellectual elite” and “[her] approach to Talks reflected her liberal and progressive viewpoint.”28 She was also a feminist, a lesbian and a Soviet sympathiser who used her position to promote the views of her friends, lovers and comrades, especially members of the subversive Bloomsbury group and the socialist Fabian Society.29 Lionel Fielden was her main producer, also homosexual, anti-imperial and a supporter of Mohandas Gandhi, whom he promoted on BBC radio in India.

According to Asa Briggs, “[t]he early members of the Talks Department introduced to broadcasting some of its most brilliant performers—Harold Nicolson, Vernon Bartlett, Ernest Newman, Stephen King-Hall, Raymond Gram Swing, and John Hilton.”30 Simon Potter adds that “Matheson invited influential and pugnacious figures from the world of politics to speak on air, including Winston Churchill and Harold Nicolson, as well as cultural figures like HG Wells and George Bernard Shaw.”31 John Hilton was “an ardent trade unionist” admired by communists including Guy Burgess with whom he later collaborated at the BBC; both were recruited into the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6).32 Nicolson, King-Hall, Bartlett and Churchill were all vociferous proponents of an anti-German foreign policy.33 Socialists were consultants as well as guests. “‘I remember best the trinity of EM Forster, Desmond McCarthy and HG Wells,’ Lionel Fielden has written, ‘who all gave us freely of their time and wise counsels, and would sit round our gas fires at Savoy Hill, talking of the problems and possibilities of broadcasting.’” 34 Nicolson was not only a guest but the husband of Matheson’s lover, Vita Sackville-West. Beatrice and Sidney Webb were central members of the Fabian Society and apologists for the Soviet Union during its most tyrannical period. George Bernard Shaw, also a Fabian socialist and Soviet sympathiser, was a proponent of racial mixing who cursed and derided ‘anti-Semites’ with the same canards used by The Times in 1882: “...Anti-Semitism is the hatred of the lazy, ignorant, fat-headed Gentile for the pertinacious Jew who, schooled by adversity to use his brains to the utmost, outdoes him in business.”35 HG Wells, another defender of the Soviets, was given BBC airtime by Matheson to advocate for a world state and the end of nations.36 Matheson’s “pugnacious figures” also included the Marxist and Zionist Harold Laski, the Soviet agent EF Wise, the ‘Red Countess’ of Warwick, the Quaker and socialist Philip Noel-Baker, Ernest Bevin, the militant feminist Viscountess Rhondda and the pro-Soviet ‘pacifist’ and Focus member Norman Angell, as well as John Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, EM Forster and others of the Bloomsbury circle. William Beveridge, a Liberal by party though a Fabian socialist in deed, “gave six talks on unemployment in 1931, following on a general series on the same subject.”37

Asa Briggs writes that “[u]nder Hilda Matheson the BBC employed speakers of every persuasion, but this did not save it from charges of ‘leftwing bias’.”38 Briggs, a pro-BBC historian, was perhaps merely re-wording Matheson’s own statement in 1933 that “[a]n impression of left-wing bias is always liable to be created by any agency which voices unfamiliar views… It does not always follow that the ideas themselves are of the left. In practice, they usually hail from every point of the compass.”39 As Ronald Coase said in 1950, “The fact that the Corporation has been criticised by the Right and the Left hardly proves, as many of its supporters contend, that it is impartial; of itself it merely shows that the Corporation has not been consistently at one of the extremes.”40 The Corporation leaned strongly to the left as soon as it began to broadcast opinionated content and was merely occasionally told to cancel one talk or disinvite a particularly aggravating speaker. I find no record of any nationalist or fascist being invited to give talks, and there were not even many Tories. All figures ‘of the right’ invited to speak on the BBC appear to have been anti-German.41 Ian McIntyre refers to Churchill as one of the “mavericks of the right”, a true if understated description in the sense that Churchill’s affectations and associations were vaguely right-wing but his deeds and legacy were the opposite.42 Lord Lloyd, first head of the British Council, an anti-fascist cultural propaganda body spun out of the Foreign Office, who spent the latter half of the 1930s agitating for war against Germany, was regarded within the BBC as of the “extreme right”.43 The BBC ‘balanced’ anti-German Soviet sympathisers with anti-German Soviet collaborators. The war, or the wars, against Germany, both of which Lloyd and Churchill supported, did more than any other events in history to empower the left and socialism, as Neville Chamberlain had predicted and striven to avoid.

Marxists and communists

Matheson’s contumacy toward Reith, especially in regard to criticism from the Daily Mail of her promotion of her comrades, resulted in her resignation. The New Statesman predictably blamed “official and orthodox pressure” which kept out “the expression of new ideas”, though “paid a tribute to the BBC as a whole” which, after all, was still a state monopoly and thus a castle to be held.44 Matheson was succeeded as Director of Talks by another leftist, the “like-minded” Charles Siepmann, of whose spell Briggs writes that “the same charges” of left-wing bias “were frequently repeated, and the Corporation found it desirable to seek ‘rightwing speakers’ who would offset criticism.”45 The dearth of such speakers actually broadcasting suggests that the Corporation went no further than ‘finding them desirable’. Instead, the socialist JB Priestley was given space for a “personal comment”, Winston Churchill warned about the ‘threat’ of Germany, and “An excellent series called Whither Britain?... was broadcast in 1934 (with Wells, Bevin, Shaw, and Lloyd George among the speakers) and this was followed later in the year by a series on The Causes of War (with, among others, Lord Beaverbrook, Norman Angell, Major Douglas—of Social Credit fame—and Aldous Huxley).”46

Eventually Siepmann, like Matheson, was, as Kate Murphy describes, “censured for being too radical”, i.e. “transferred to the role of Director of Regional Relations” in 1935.47 Hilda Matheson objected in the Observer, seeing him as her continuation.48 In Siepmann’s new remit, the largest of the BBC’s regions was BBC North, for which the Programme Director, EAF Harding, on his appointment in 1933, had “raided the Manchester Guardian” for its journalists “and with the full co-operation of WP Crozier, the editor” had drawn upon “the services of a number of the Guardian’s leaderwriters and reporters as North Regional broadcasters.”49 The strongly left-wing Guardian is the newspaper most read at the BBC today, vastly out of proportion to its sales to the public, and the BBC long sought to recruit to the greatest extent possible from among Guardian readers. Under Siepmann, John Coatman had been “deliberately brought in” by Reith for the role of the BBC’s Chief News Editor “as ‘right wing offset’ to ‘balance’ the direction of talks and news” but “showed no sign of doing so”; Coatman “insisted on his own independence as a maker of policy”.50 Richard Maconachie, “a man of conservative views” became Head of Talks in 1936, formally senior to the Director of Talks. According to Ben Harker, “His Director of Talks, Norman Luker, was by contrast a liberal intrigued by the far left” who “was keen to create a platform for a Marxist analysis of the issue” of class and wanted to reorient talks to appeal to the same audience as the anti-fascist Picture Post, edited by Istvan Reich, a Jewish political exile from Hungary, and the Left Book Club run by the Jewish communist publisher Victor Gollancz. Luker was a long-standing friend of the Cambridge Apostle, homosexual, Soviet spy and producer at the BBC, Guy Burgess. The robustness of the “right-wing offset” was evident in the rejection of Luker’s preferred Marxist lecturer, the Cambridge communist don Maurice Dobb; instead Luker had to settle for Arthur Horner, a member of the Communist Party’s central committee and a trade unionist. Dobb had, at any rate, already appeared “periodically” on the BBC earlier in the decade. Horner, in his broadcast in November 1938,

“ranged freely from Marx’s theory of class struggle as the engine of history, through to an explication of the Communist Party’s line on fascism, to a description of the Spanish Civil War as militarized class struggle, and into a justification of the Moscow Trials as revolutionary justice against counter-revolution. His talk, which was published unedited in the BBC’s in-house magazine The Listener, concluded with a familiar Popular Front appeal for what he called ‘the cultural, clerical and professional classes’ – generally the assumed audience for National Programme Talks – to come over to the working class in the struggle against capital and fascism.”51

BBC North

The BBC also issued Marxist propaganda via other avenues. As Ben Harker describes, communists coveted the BBC’s “growing cultural and political influence in the 1930s” which drew upon “its increasing significance in the construction of British identity, notably in its power to fashion the national narrative.”52 Fortunately for them, when the Corporation began to establish regional divisions in 1933, BBC North, the largest, became a “cauldron of Marxist and left-wing mischief” under its first Programme Director, the avowed Marxist EAF Harding.53 The producer Olive Shapley, the folk singer AL Lloyd, the thespian and director Joan Littlewood and her husband the singer and actor Ewan McColl (born Jimmie Miller) were central figures and all were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. According to Shapley, Harding was also a “comrade”.54 The North producer Geoffrey Bridson was merely a close friend and a sympathiser who didn’t join the party but was introduced to Harding by the Comintern propagandist Claud Cockburn, inventor of the myth of the Cliveden Set.55 Shapley, though she left the party after university (as did Guy Burgess), continued as an agent of the cause, moved to New York in 1941 and interviewed guests like the subversive Eleanor Roosevelt and the singer Paul Robeson, later winner of the Stalin Prize, for the BBC’s Children’s Hour. According to Harker, “It was Harding’s view that all radio was propaganda: broadcasts which failed to give voice to the working class silenced it, those which failed to address structural inequalities shored up the status quo.”56 Harding broadcast propaganda without subtlety. Documentaries like May Day by Bridson simply issued a communist reading of history, one which led inexorably toward The Revolution.57 The North team produced programmes about Chartism that coaxed the listener toward the same conclusion: working Britons had not yet completed their revolution. The Classic Soil, proudly memorialised by the BBC today, was an overt vindication of the 19th century writings of Friedrich Engels, co-author of the Communist Manifesto and Capital, read by Ernst Hoffman, an anti-fascist immigrant from Germany.58 Shapley, the producer, later described her own work as “probably the most unfair and biased programme ever put out by the BBC”.59

Soviet espionage

From its founding in 1917, the Soviet Union had engaged in ceaseless attempts to dissolve and undermine Britain and the empire, using the Comintern, espionage, front groups and the assistance of sympathisers.60 As John Costello says, referring to the late 1920s and early 1930s, “Stalin’s lust for obtaining secret intelligence endowed [the] OGPU and its “organs” with unrivaled power, and he stepped up the pressure to expand the penetration of foreign governments. The primary target was Britain—the main adversary, in Stalin’s eyes[.]”61 The OGPU was the successor of the Cheka and predecessor of the NKVD and KGB. The Soviet penetration strategy came to centre upon upper-class students at Cambridge and Oxford who were best-placed to enter the civil service; the infamous ‘Cambridge Five’, and others better concealed, were thus recruited. With some awareness of the threat, the most conservative elements at the Security Service (MI5) held meetings with the BBC in 1935 which “set in motion a system of political vetting” to cover new BBC employees which was “formalised with a written agreement in 1937.”62 The vetting was insufficient; anyway, MI5 itself had employed subversives like Hilda Matheson during the Great War and since.63 The Soviet spy Guy Burgess was appointed as a producer of BBC Talks in June 1936 and was recruited to work for MI6 during his time there.

The intelligence services contained genuine opponents of the left, but the social worlds of their agents, Foreign Office employees and other civil servants, Cambridge Apostles, overt and covert communists, the Bloomsbury group, and upper class homosexuals all appear to have blended together, as is exemplified by Burgess himself. Burgess later made Anthony Blunt, a fellow Apostle, homosexual and Soviet spy, a frequent guest on the BBC, and elevated the already-high status of the bisexual anti-fascist Harold Nicolson at the corporation. Jews were prominent in the same circles. Burgess met the philosophers AJ Ayer and Isaiah Berlin, both later to work in MI6, at a dinner party hosted by Felix Frankfurter.64 Victor Rothschild, the third Baron Rothschild, was another Apostle; according to Victor’s sister Miriam, Burgess was one of “the many people” whom her mother Rózsika, “assisted or supported by periodic and regular payments” for unclear reasons. Another was the Comintern agent Rudolph Katz.65 Victor Rothschild joined MI5 in 1939 (or before); the following year, Anthony Blunt was recruited on Rothschild’s recommendation.66

The suitability of Cambridge University as the prime location for Soviet recruitment owed much to the concentration of homosexuals among teaching staff and students. The Apostles, who included the amoralist philosopher GE Moore and others of the Bloomsbury group, had in earlier decades become “obsessed by homosexuality”, and several members “pursued what they called ‘the higher sodomy.’”67 “Higher” referred to their disdain for romantic love as well as their general sense of superiority. The Apostles were already a secret society, and homosexuality was actively prohibited in Britain until the 1960s. Some of those who practiced it formed “extensive underground ‘old boy networks’” which “reached out like a cobweb across the pinnacles of the British Establishment, with connections in Whitehall ministries, the universities, the foreign service, the church, and the armed services”; “several of the lines of this web of homosexual influence were spun by Apostles who, by the twenties, had anchored themselves firmly in the upper reaches of Whitehall” and “offered great opportunities to any blackmailer—or spy—who gained admission.” Jack Hewit, a lover of Burgess, first met him at a homosexual party in the War Office in 1936 at which Rudolph Katz was a guest.68 Burgess was extremely promiscuous and engaged in exchanges of love letters with ‘conquests’ to use as compromising material.

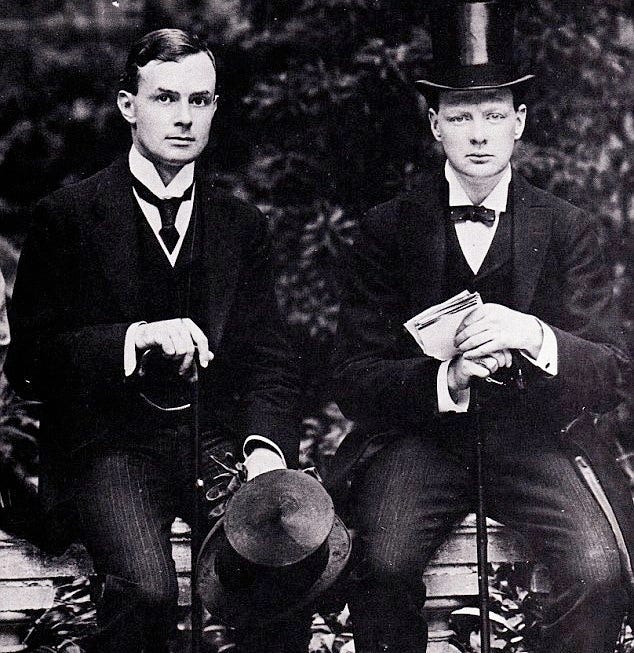

John Costello identifies Edward Marsh as “the leading behind-the-scenes string-puller in the interwar years” who “ascended the senior ranks of the civil service while pursuing his avocation as one of London’s leading literary impresarios”. Marsh

“was always ready to pull strings and arrange favors for eligible Cambridge men of intellect, talent, and good looks. Successive generations of Apostles, including Blunt and later Guy Burgess, discovered this to their advantage. The Marsh network included bureaucrats, publishers, parliamentarians, and prominent members of London society. Marsh was longtime personal secretary to Winston Churchill, to whom ‘dear Eddie’ would attach himself like a faithful hound whenever Churchill had a ministry.”69

Much of the same was true at Oxford University, where prominent dons like Maurice Bowra, aware of their closeness to Soviet intelligence agents, referred to themselves as being in the ‘homintern’; Bowra referred to Wadham, his college, as Sodom. During the Second World War he became a frequent guest on the BBC. Marxist members of the homosexual networks based in Cambridge, Oxford and London, including Roger Fulford and Kemball Johnston, attained positions in MI5 where they were able to influence their superiors in favour of members of the Communist Party.70

Popular Front

Though some communists may have been excluded from working at the BBC by MI5’s vetting, the corporation’s programmes were already used to support an effectively pro-Soviet foreign policy long before 1937. Winston Churchill is cited as one of a few right-wing speakers who disprove that the corporation was left-wing, but he exceeded the BBC in its fervour for the anti-German cause. In November 1934, Churchill was invited by the BBC to broadcast a speech in which he forebode the “destruction of the British Empire” and “Teutonic domination” of “our people” unless Britain sought allies to achieve “[p]eace… founded upon preponderance” by “mak[ing] ourselves at least the strongest Air Power in the European world.”71 This was, not by chance, the same demand as that of the civil service faction headed by Robert Vansittart and Warren Fisher that furtively supplied Churchill with false estimates of Britain and Germany’s military strengths.

The week after Churchill’s radio speech, the British arm of Samuel Untermyer’s Anti-Nazi Council was founded, and the following October it held a large demonstration in Hyde Park; the BBC broadcast the speeches by Eleanor Rathbone, Clement Attlee, Walter Citrine, JBS Haldane and Sylvia Pankhurst, all socialists or communists. There was no BBC Talk given by Oswald Mosley to ‘balance’ Churchill and no coverage of demonstrations against communism or hostility toward Germany. The BBC covered the events of the largest such demonstrations, those of the British Union of Fascists, by spotlighting the blackshirts’ eviction of hecklers and invaders. The BUF’s Olympia rally in 1934 occurred at the same time the BBC began to be allowed to create its own news reports. The ludicrous myth of the BUF intentionally causing violent disruption of its own events has endured.

From 1936, BBC Television broadcast selected newsreels from Gaumont and Movietone, the latter being a subsidiary of Wilhelm Fuchs’ Fox Corporation and the former owned by Isidore Ostrer. Ostrer was, according to Nicholas Pronay and Philip Taylor, “the most skilful and clear-minded manipulator of the propaganda potential of the newsreel”; as Gaumont also produced films and owned many cinemas, the effect of his skills was amplified greatly.72 Fuchs and Ostrer were both descended of Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. The British film industry and cinemas were largely Jewish-owned through the 1920s and 30s.73 Burgess, before being hired by the BBC, was recruited to work for the Soviet NKVD probably by Arnold Deutsch, a cousin of Oscar Deutsch, the founder and owner of Odeon Cinemas and a referee for Arnold’s immigration application.74

The BBC, especially the North division, effectively joined the Popular Front, a Soviet anti-fascist initiative, and thereby aligned with the aims of the international Jewish alliance agitating for regime change in Germany and with organised Jewry in Britain, whose activists secured special privileges. According to Geoffrey Alderman, “An agreement… was reached with the BBC which undertook to submit” to the Board of Deputies of British Jews “the scripts of any programme “of Jewish interest” before the programme was broadcast.” The agreement was part of the Board of Deputies’ Defence Committee’s anti-fascist strategy which also included “intelligence-gathering, media-monitoring and co-operation with the Special Branch.”75 In the spring of 1938, recalling 1881, “a Mansion House Fund and innumerable appeals on behalf of refugees from Austria, Germany and Czecho-Slovakia were broadcast from the BBC and in the British Press.”76

According to William West, “The BBC and its staff… took an essentially Communist line” at the time of the Spanish Civil War which indicates how “the more sinister activities of Burgess and his circle remained unremarked.”77 During the Sudetenland crisis of September 1938, Burgess was the producer responsible for planned anti-German speeches by Harold Nicolson which were cancelled under pressure from the Cabinet Office, which was loyal to Neville Chamberlain, and the Foreign Office under Halifax who was still for peace with Germany at the time.78 Producing ostensibly non-political programmes about the countries of the Mediterranean, Burgess also collaborated with the Marxist academic EH Carr and tried to involve Winston Churchill, of whom he was “a keen supporter” though the latter withdrew in anger at being required to moderate his belligerence.79 According to West, “the line followed by Burgess and EH Carr in the BBC’s Mediterranean series was close to [Anthony] Eden’s…”.80 Eden “had broadcast to the world his welcome” of the Soviet Union to the League of Nations in 1934 and, alongside Churchill, was the most prominent Tory supporter of an alliance with the Soviets; Eden was particularly friendly to Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister, while Churchill liaised more with Ivan Maisky, the ambassador in London to whom he had been introduced by Vansittart.81 In contrast to its pro-Soviet slant, the BBC refused to broadcast or even acknowledge the impassioned radio speech from Verdun by the Duke of Windsor, the abdicated King Edward VIII, for peace between Britain, France and Germany in May 1939.82

Propaganda and black operations

As the BBC aligned with Jewish and Soviet policy, it applied its “power to fashion the national narrative” in accordance with the propaganda bodies of the British state, staffed and governed increasingly by anti-fascists, which were used to counter Italian and German (not Soviet) propaganda. The most overt, the British Council, was an initiative of Rex Leeper, head of the Foreign Office’s News Department and payee of the Soviet-aligned Czech government, who introduced Churchill to the Anti-Nazi Council, which Churchill renamed the Focus, in April 1936. The BBC’s Empire Service and foreign language broadcasting were launched to work to the same purpose as the Council. Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, but the propaganda war was underway at least two years earlier when the Focus member Lord Lloyd, another figure of the “extreme right” who sided with the extreme left in foreign policy, became chairman of the Council.83 Anti-fascism and sympathy for the Soviet Union were already embedded institutionally in Britain long before the Anschluss, ‘Munich’ or Kristallnacht.

Section D of MI6 was created in March or April of 1938 “to provide lines of communication for covert anti-Nazi propaganda in neutral countries”, to “organise and equip resistance units, support anti-Nazi groups” and enact “sabotage, covert operations, and subversive propaganda.” Guy Burgess was employed by Section D, the first of a chain of propaganda bodies established by the British state which presented Jewish emigrants from Central Europe as friends of and spokesmen for Britain. Vansittart, Claude Dansey of MI6, Churchill and the Focus had been using the same people for (often fabricated) intelligence and propaganda for some years. As Andrew Lownie describes, “Section D used a series of front organisations, such as the news agency United Correspondents, which produced innocuous but anti-Nazi articles for circulation to newspapers around the world, and Burgess worked with writers such as the Swiss journalist Eugen Lennhof and the Austrian writer Berthe Zuckerkandl-Szeps.”84 In Section D, John Costello says, “Burgess appears to have been the main fount of ideas and principal producer of clandestine programming. In compiling the careful assembly of propaganda talks, variety shows, and hit records, he was assisted by Paul Frischauer, an Austrian refugee, and his wife, who were members of an anti-Hitler group in London.”85 The “radio war” consisted initially of illegally broadcasting Chamberlain speeches into Germany on Radio Luxembourg, owned by Isidore Ostrer and run by Eva Siewert, a Jewish lesbian and Soviet sympathiser.86

The covert counterpart of the British Council and an adjunct of MI6 and the BBC was the Joint Broadcasting Committee, which operated in sufficient secrecy as to be unknown to MI5. According to Lownie, “The JBC was very much a BBC operation. It was run by Hilda Matheson… assisted by Isa Morley, the foreign director of the BBC from 1933 to 1937. Burgess was number three and represented Section D’s interests. In March 1939 Harold Nicolson joined the Board.” Angus Hambro, a Tory MP from an established Jewish banking family, was also a member. “JBC staff were authorised to use BBC studios”, and though “scripts were prepared by JBC staff, many were read by prominent exiles such as the writer Thomas Mann, or later by well-known actors such as Conrad Veidt”, both married to women of Jewish ancestry. Burgess also recruited John Bernal, a Jewish communist and a science don at Cambridge, as well as Edvard Benes, the former Czech Prime Minister and a friend and ally of Stalin, to record speeches for the JBC.87

There was, in retrospect, no chance that BBC and its Talks and News output would ever be anything other than left-wing, pro-Jewish and anti-fascist. Since before it began to broadcast opinion pieces and news, the BBC was populated by “fanatics” like Charles Siepmann and Hilda Matheson who posited the myth of the “ultra-conservatism of the culture” and the “old Conservative clique” as needing redress by their own “progressive policies” and “subversive theory of balance”. Such people never willingly yield institutions of which they have taken control, and instead of facing any threat of being turfed out, they were then and are now confronted only by flaccid or traitorous Tories. The BBC, as Tom Mills says, “is part of a cluster of powerful and largely unaccountable institutions which dominate British society – not just ‘a mouthpiece for the Establishment’ as Owen Jones suggests, but an integral part of it.” Neither Mills nor Jones, though, would acknowledge that the Establishment was already by the early 1930s partly, and the BBC almost entirely, controlled by socialists, communists, globalists, homosexuals and Jews. Reith and Chamberlain headed the broadcaster and the government but did not prevent their ‘crusading’ subordinates having their own way. While communists and fellow travellers staffed the Corporation and amplified themselves and their comrades, not only were fascists or nationalists entirely excluded, but even the views of those who supported Chamberlain and peace were barely heard. The weakest period for the anti-fascists was in 1938, as Chamberlain’s Cabinet Office actively subdued them; Guy Burgess resigned from the corporation in frustration. Yet after Lord Halifax joined the war party, Chamberlain was isolated in the Cabinet and Parliament and cornered into adopting anti-German policies. The ensuing war enabled Churchill to form not only a government in May 1940, but a new anti-fascist regime which has ever since imposed a false version of history via the BBC and the education system. The ‘maverick of the right’ was the best friend the left have ever had.

The Birth of Broadcasting, Asa Briggs, 1961, p180-2. Reith sought to apply the “brute force of monopoly” beyond Britain, as British law alone could not prevent commercial stations broadcasting into Britain from transmitters abroad, which they did through the 1930s. The BBC lobbied via the International Broadcasting Union for the greatest possible restrictions on Radio Luxembourg, Radio Normandie and others, and did so with the support of the Newspaper Proprietors’ Association, but Radio Luxembourg exceeded the BBC’s listening figures at times and only ceased operations when its facilities were effectively nationalised after Britain and France declared war on Germany in September 1939. Under Reith, the BBC had only broadcast for a few hours on Sundays and the content was mostly religious while Radio Luxembourg played more dance music. See The Golden Age of Wireless, Asa Briggs, 1965, p92, 360.

The Golden Age of Wireless, Asa Briggs, 1965, p433. Briggs is paraphrasing the Labour politician and BBC governor Mary Agnes Hamilton.

The BBC: Myth of a Public Service, Tom Mills, p21. See also p5, 23

Mills, p25

Briggs, Golden Age, p419.

Briggs, Birth, p246

The BBC, Asa Briggs, 1985, p72. My emphasis.

Briggs, Birth, p292

British Broadcasting - A Study in Monopoly, Ronald Coase, 1950, p188-9

Dolphins are discussed with an approving voice and jolly music; the ‘far right’ is mentioned in an alarming tone with sinister music.

The Expense of Glory, Ian McIntyre, 1993, p70

McIntyre, p99, 217, 250. ‘The Trumpet of the Night’: Interwar Communists on BBC Radio, Ben Harker, History Workshop Journal, Volume 75, Issue 1, Spring 2013, p82

McIntyre, p270

Briggs, Golden Age, p57

Briggs, Golden Age, p13. Briggs is quoting Hilda Matheson.

Briggs, Golden Age, p39

Briggs, BBC, p53

Coase, Study, p163

About lifting the ban on controversial broadcasting, see Coase, Study, p62

Briggs, Golden Age, p13. One early element of the “social and cultural crusade” was to expose the public to subversive artists, writers and musicians. In music, as Asa Briggs describes, the BBC chose “the hazardous enterprise of introducing to the British listener Schönberg and Webern as well as Bartok and Stravinsky. In music it was always among the avant-garde…” Briggs, Golden Age, p171-2

Charles Siepmann interviewed by Harman Grisewood in 1978. Siepmann was later paid to move to the USA by the Rockefeller Foundation and wrote a paper for the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith.

Briggs, BBC, p115

Briggs, Golden Age, p219. Harold Laski was the brother of the head of the Board of Deputies of British Jews from 1933 and son of the man who “enlisted” Winston Churchill to campaign for open borders in 1904.

McIntyre, p190

Glamour Boys, Chris Bryant, 2020, introduction

Briggs, Golden Age, p124. “The place of adult education in the BBC’s central organization was never secure. In February 1931 it hived off from the Talks Department and became a separate department under the direction of Siepmann; in February 1932 it became a department of a new Talks Branch when Siepmann replaced Hilda Matheson as Director of Talks; in September 1934 it was fully merged in the Talks Branch, losing its departmental identity. Behind these vicissitudes there were not only personal differences but deeper uncertainties about what exactly was the relationship between talks and organized adult education.” Briggs, Golden Age, p222

Behind the Wireless, Kate Murphy, 2016, chapter on Hilda Matheson

Harker, p87

Briggs, Golden Age, p126

The Mask of Treachery, John Costello, 1988, p317-8 and p590

Harold Nicolson was the son of Arthur Nicolson, a diplomatic protégé of King Edward VII. Stephen King-Hall was a future Labour MP and publisher of the anti-German London Newsletter which shared an audience with publications of the Focus and the Comintern; he was “a frequent broadcaster”. Briggs, BBC, p119

Briggs, Golden Age, p127

Bernard Shaw, Michael Holroyd, 1998, chapter 2, 3. Shaw “was to define fascism as ‘State financed private enterprise’ or ‘Socialism for the benefit of exploiters’. From the 1930s onwards Shaw chose to call himself a communist: ‘that is, I advocate national control of land, capital, and industry for the benefit of us all. Fascists advocate it equally for the benefit of the landlords, capitalists and industrialists.’”

Briggs, Golden Age, p126-7. Wells speaking on BBC radio. The Listener praised Wells as a man “who can see the future”; presumably the producers who chose him were prescient too.

Briggs, Golden Age, p41

Briggs, Golden Age, p141

Briggs, Golden Age, p43. Matheson continued: “How is the inevitable fear they provoke to be reconciled with the spirit of open-minded enquiry which is inseparable from all education, from any search after truth?’”

Coase, Study, p188-9

I have not found any counter-examples.

McIntyre, p188

Briggs, Golden Age, p470-1

Briggs, Golden Age, p43

Briggs, Golden Age, p141; Harker, p87

Briggs, Golden Age, p143-4. Beaverbrook, the most ‘right-wing’ of these, often dined with the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky, employed the anti-fascist cartoonist David Low and joined the wartime government in May 1940 after Churchill became Prime Minister. He also served in the wartime Cabinet in 1918.

Murphy, chapter on Hilda Matheson

Mills, p40

Briggs, Golden Age, p330

Briggs, Golden Age, p118, 147

Harker, p87-8

Harker, p92

Audio Drama Modernism, Tim Crook, 2020, p264

Interview with Olive Shapley, 1984, p3-4 and Broadcasting a Life, Olive Shapley, 1996, p37. From the latter, referring to her first meeting with Harding where he asked her to stay behind: “‘When the room was empty apart from the two of us, he extended his hand and said, “Welcome, comrade.” I was never a very devout communist, but I could tell that I was among friends.’”

Harker, p89

Harker, p90. How exactly the middle-class Shapley interviewing the wealthy Roosevelt gave voice to the working class is unclear.

Harker, p92

Harker p93. Marx only completed the first volume of Capital by himself.

Shapley, Broadcasting, p54. The BBC’s programme index lists Engels as a contributor to the programme.

Though they had small resources and were about to engage in war on several fronts, the Bolsheviks commenced espionage against Britain immediately after the coup. Chapter 5, ‘Exporting the Revolution’, of John Costello’s book The Mask of Treachery gives a summary. See also chapters 1-5 of Giles Udy, Labour and the Gulag.

Costello, p182

Mills, p42. “The practice was maintained for fifty years, abandoned only in 1985 after being exposed by a team of investigative journalists. Much of what is known about political vetting, stems from the revelations at that time and the declassified BBC files that have become available since.”

MI5 now names Hilda Matheson as a “lesbian role model”.

Stalin’s Englishman, Andrew Lownie, 2015, chapter 5

Costello, p299-300. Costello suggests that Burgess worked for the Rothschilds’ own intelligence network as well as MI6 and the NKVD:

“Since private intelligence was an essential element of the Rothschild business operation, what better cover could they give their latest recruit in 1935 than to characterize Burgess as an investment counselor and dispatch him as their private spy to monitor the Anglo-German Fellowship? Information about threats to the House of Rothschild resulting from secret deals between British sympathizers and the Third Reich would more than justify the hundred guineas a month paid to Guy Burgess.

Victor Rothschild had implicit faith in his Cambridge friend because he, like Blunt, knew of Burgess’s true loyalties. But Burgess’s volatile enthusiasms would help persuade his right-wing friends that he had recanted his earlier Marxism. His homosexual appetite would prove an exploitable talent when it came to sharing the bed of a pro-German Tory well placed to pull strings and advance an ambitious young man’s career. Nor should it be forgotten that Rudolph Katz, with his own extensive network of homosexual and Comintern contacts, also contributed to Rothschild’s private intelligence network that, at the time, shared with Stalin a common enemy: Hitler.” Costello, p303-5

Lownie, chapter 17; Costello, p369-71

Costello, p143

Costello, p307-8

Costello, p65, 150-1. See also Churchill’s War, volume one, David Irving, 2003, p26-7

Costello, p427-30

Winston Churchill - the Greatest Briton, Parliament Archives. Churchill - “After he had given his talk in the 1934 Causes of War series there were complaints that he had delivered a ‘gratuitous attack on Germany’, and one writer said that it was ‘in need of far more censorship than Professor Haldane’s’, a talk on the extreme left.'” Briggs, Golden Age, p146

'An Improper Use of Broadcasting...', Nicholas Pronay and Philip Taylor, Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 19, Number 3, July 1984, p368

Edward Marshall in New Directions in Anglo-Jewish History, edited by Geoffrey Alderman, 2010, p163-8

The Defence of the Realm, Christopher Andrew, 2009, p171

The Czech Conspiracy, George Henry Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers, 2003. Rothschild used a speech at Mansion House to invoke “the slow murder of 600,000 people” (German Jewry). It is not clear that even one thousand had yet been murdered in the nearly six years of Hitler’s regime.

Truth Betrayed, WJ West, 1989, p40. Burgess’ friend Kim Philby, who worked for MI6 and the NKVD simultaneously, was The Times’ correspondent during the civil war and MI6’s head of undercover operations in Spain and Portugal during the world war. Burgess and Philby both worked for MI6’s propaganda-focused Section D and, like Eric Maschwitz, the sabotage-focused Special Operations Executive in 1939 and 1940. In 1934 Philby had married Litzi Friedmann, a communist from Vienna and an associate of the Soviet spy Edith Tudor-Hart. By 1941, when Burgess rejoined BBC Talks, the corporation was under the control of Churchill’s government and hired Burgess precisely because he was pro-Soviet.

West, p138-40

West, p54-7. Burgess recorded his recollection of visiting Churchill’s mansion Chartwell.

West, p106

According to Chris Bryant, Vansittart was “married but predominantly homosexual”, though Bryant does not give a source. Bryant, chapter 11

In November 1938, according to the ambassador to Italy, Eric Drummond, the 7th Earl of Perth, BBC presenters used tone of voice to mock Chamberlain and praise Anthony Eden. West also says that “There had been a number of concerted attacks on Chamberlain by the BBC, usually in the form of selective reporting of speeches and debates.” See West, p166, including note 101.

Briggs, BBC, p141; Briggs, Golden Age, p397 to 408

Lownie, chapter 13

Costello, p331

Alderman, New Directions, p165. See also West, p111. Reith had been the leading advocate of the International Broadcasting Union, in the violation of which the BBC now collaborated.

Lownie, chapter 13. The JBC had a “strong focus” on “securing British propaganda broadcasts on the American networks.” American networks also had their own plans. “The covert side, where Burgess largely worked, produced programmes for distribution in enemy countries, working with Electra House. Burgess was responsible for a variety of programmes that were recorded on large shellac discs and then smuggled in the diplomatic bag or by agents into Sweden, Liechtenstein and Germany, and broadcast as if they were part of regular transmissions from the German stations themselves.” The ‘Chaos of the Ether’ had gone from a myth to a tactic. About the JBC, see also Murphy, Behind the Wireless, chapter on Hilda Matheson, and West p118, 140.

What a disgusting cast of anti-British actors. It makes one wonder what on earth the old establishment were doing in the first half of the century. Perhaps the subversion came too fast and was too embedded to dislodge by the time that the likes of Moseley entered the stage?

Hi Horus,

Many thanks for your thorough explanation. What puzzles me is the absence of purges. Once the importance of subversion is understood, why did Neville Chamberlain and his supporters keep Reith ? Why did they not change the top management and enact a large scale purge of the homosexuals, Fabians, Soviet sympathisers, Jews, and the ilk ? This passivity is astonishing.

In the same era, the Catholic Church was also passive towards infiltration and subversion. Under Pius XI several large scale enquiries identified networks of communist priests and bishops in relation with the Comintern, members of the free masonry, subversive theologians. One such enquiry was headed by the future Pius XII. Yet both popes took very little action, mostly ordering people to stop preaching or teaching subversive ideas. No purges.

In contrast the progressive adversaries have never had any qualms about purging conservatives and promoting their ilk.