Hitler’s violation of the Munich settlement in March 1939 proved his perfidy and his intention to conquer. But why was Britain party to that settlement? The German invasion of Poland triggered the declarations of war by Britain and France. But why were those countries allied with Poland? The two statements are familiar. The two questions I arrived at myself, and since the answers have not been forthcoming from historians, I have sought them, and only thereby begun to understand the causes of the war.

To say that the war began because Germany invaded Austria, Czechoslovakia or Poland leaves begging any explanation of British involvement, as Britain only pledged support to Poland six months before the German invasion and was never allied with Austria, Czechoslovakia or France. The latter two were allied with each other since 1924, and both made pacts with the Soviet Union in the 1930s. France’s alliance with the Czechs (who dominated the Slovaks) made Germany’s demands toward the latter a British issue because British politicians and civil servants informally maintained the Entente with France: the unwritten understanding that the two would act together (with Russia) against Germany. The understanding was formed in 1904; the Great War had occurred, Russia had been superseded by the Soviet Union and Germany had been diminished at Versailles, yet through the succeeding twenty years, albeit with serious differences, Britain maintained a common diplomatic front with France against Germany. French politicians’ hostility to Germany and collaboration with communists was condoned and imitated by the war party in Britain. French politicians, exploiting British sympathy, aggravated relations with Germany and surrounded it with alliances, but refrained from declaring war alone, regarding British commitment as a necessity. Pro-war forces in Britain required six years to discredit, isolate and defeat the moderates and peacemakers; when they did so, Britain declared war and France followed.

A year before, Britain had been the decisive actor at the Munich summit, in which Czechoslovakia was, according to Churchillian history, ‘given away’ to Germany in a vain attempt to avoid war. Why war would otherwise have eventuated and between whom tends to go unspecified. France was unfaithful from the start in its promises to the smaller nations and would have forgone them if Germany’s threats to Czechoslovakia were fulfilled. Britain’s solidarity was precisely what made France and the Czechs affect such boldness as they did. British politicians, including Neville Chamberlain, acted there, and before and after, as though allied with France; for this I have never encountered any explanation. A self-consciously pro-French, anti-German faction fostered by King Edward VII took over the civil service, Parliament and the media in the century’s first decade and brought about the First World War, in which Churchill exulted. As nothing appears to have interrupted the hold of that faction on British policy, I surmise that they and their successors deepened their power through the 1910s and 1920s, became what we now call anti-fascists in the 1930s and have had hegemony in politics and the publishing of history ever since.

There should be detailed accounts written on this continuation of British support for France against Germany in the interwar period, as it was probably the most consequential foreign policy option in modern British history. Instead the most famous historians have, since the war, directed their readers’ attention toward whatever justifies the course taken by Winston Churchill, not only as Prime Minister from May 1940 but in the previous seven years through which, in their portrayal, he was a prescient but unheeded seer of the German threat. Historians who have diverged, like David Irving and Patrick Buchanan, are treated not only as incorrect but as fools or scoundrels to be met either with vehement denunciation or aloof avoidance and disparagement. In the telling of court historians, Hitler’s insane and malevolent actions are always the explanation for the war. Only one party instigated conflict; everyone else involved was merely responding to the ‘Nazi menace’; every other factor cited is Nazi apologism.

National chauvinism could explain using such a selective approach to exonerate Britain and France, but it is also taken by Western historians in favour of the Soviet Union. The Soviets, it is implied, were no threat to anyone (until 1945). The numerous attempts at Marxist overthrows in Germany, Switzerland, Poland, Hungary, Romania and other states since 1917 are mentioned only in the more detailed studies of the time, yet these were the primary provocation for the burgeoning of fascism and national socialism, which decidedly are included in the victors’ history as causes of the war. The ubiquity of the myth, probably Trotskyist in origin, that Stalin gave up on the idea of world revolution (or conquest) is convenient for his apologists in the West. ‘Socialism in one country’ derives from one letter to a newspaper by Stalin; it is belied by his and others’ more private utterances and the gargantuan military forces he amassed through the 1930s and positioned at the border with Germany in 1940-1, ready to convey socialism to many more countries.

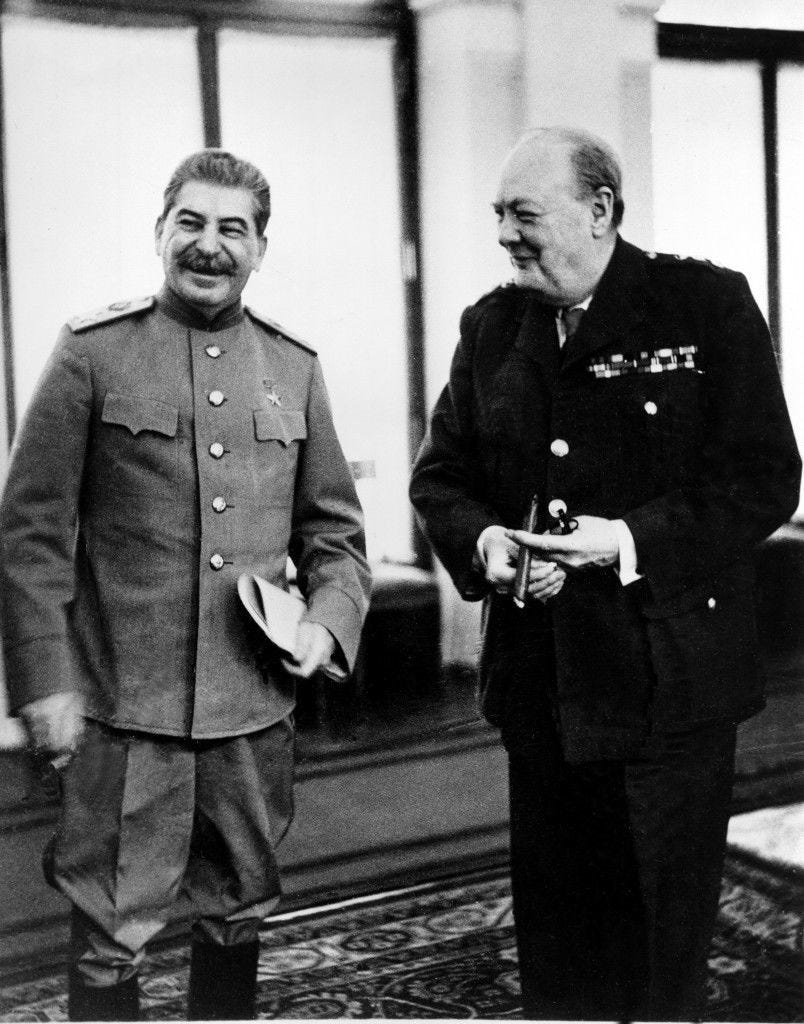

The activities of the Comintern and the Soviet NKVD in penetrating the British civil service and recruiting agents of influence and prestigious non-communist advocates via front groups are the subject of dozens of books, television dramas and movies, yet I know of few historians who make any mention of them in relation to the causing of the war. Those Churchillian historians who mention the most famous Soviet foreign initiative, the Popular Front, condone it at least tacitly. They could hardly do otherwise, as Churchill was effectively part of a greater anti-German alliance of which the Popular Front was a vital international element. Churchill’s phrase from 1941 about being willing to make a favourable reference to the devil if the devil happened to be at war with Germany is proferred to superficial readers to imply that he became pro-Soviet out of necessity in light of Operation Barbarossa, but Churchill began to privately meet Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador, a full seven years earlier. He was introduced to Maisky specifically to foster an anti-German rapprochement by Robert Vansittart, who personified the pro-French, anti-German faction preeminent in the civil service.

By another civil servant, Reginald Leeper, and for the same purpose, Churchill was also introduced to the Anti-Nazi Council, which he renamed the Focus in Defence of Peace and Freedom (or simply the Focus). The Anti-Nazi Council was the British arm of an international campaign initiated by Samuel Untermyer to force regime change in Germany, initially by boycott. Untermyer, Felix Frankfurter, Bernard Baruch, Henry Strakosch, Eugen Spier and Robert Waley Cohen are the most well-documented of many wealthy Jewish activists who supported and collaborated with Churchill in this effort. As the boycott was found insufficient, threats of war, then war itself, became the methods required; as Britain was as yet governed by men like Chamberlain still inclined to value British interests higher than Jewish ones, regime change was required here too.

The pretext consisted in persistently characterising Germany as a threat to Britain. Churchill’s reputation as the Cassandra who ‘warned us of the danger’ refers to his speeches in Parliament and on the BBC from 1934 claiming that the Germans were developing a larger air force than Britain and implying that they would, when ready, launch it all at Britain, whom against all evidence they were supposed to revile. The juvenile preposterousness of his fear campaign should not distract from the fact that much of the intelligence he (and later the Focus) cited was simply made up by Soviet agents like Jurgen Kucyznski, brother of the handler of the traitor Klaus Fuchs. Germany had no plan to bomb Britain and appears not to have prepared for any such conflict until Churchill’s lies were several years old and beginning to generate the desired antagonism.

The Focus, covert in itself, published and staged events under aliases including ‘Arms and the Covenant’, which referred to its members’ calls for accelerated rearmament (without regard to affordability) and the enforcement of the Covenant of the League of Nations against Germany. When the Soviet Union later violated the Covenant to invade or annex five member states of the League, this approach was abandoned, but Britain was by then at war with Germany. Support of the League had always been a leftist cause and a vehicle for ‘internationalism’, i.e. the supersession of nations, an aim remarkably compatible with the long-term goals of both the Soviets and Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s vision for the United Nations after the war was as a world government with the USA and the USSR as the leading powers. The entry of the latter into the League had been welcomed by leftists, including Tories like Anthony Eden, who became Churchill’s wartime Foreign Secretary and his successor as Prime Minister in 1954.

The Second World War was the decisive moment of the left’s ascent to power in the West. Historians like Niall Ferguson and Andrew Roberts, whose careers centre upon justifying it, are falsely presented by fellow anti-fascists as conservatives. The raison d’etre of the fake right is to occupy any space in which genuine, committed opponents of the left would otherwise exist and to continually surrender. They conspire in the anti-fascist monopoly; the real right are excluded from all institutions.

The Churchillian version of history relies entirely upon portraying Germany as a threat to Britain. No matter how much the wickedness of ‘Kristallnacht’ is magnified in significance, atrocities against civilians in the 1930s cannot suffice as a casus belli against Germany, since the Soviets eradicated more of their own people every few hours throughout the decade than Hitler’s regime killed on those two nights. Aggression toward neighbouring countries also fails as an explanation. Germany invaded the western side of Poland on September 1st 1939; the Soviets invaded their agreed portion sixteen days later. Whatever excuse remained for continuing to treat Germany as the sole enemy thereafter surely evaporated when the Soviets attacked Finland and then subjugated Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Yet by the time Britain ‘betrayed’ the Baltic, at least no less than it betrayed the Czechs, Churchill and the war party were powerful enough to elide the paradox. By Churchillian historians, Hitler’s peace overtures are dispelled by asserting either that they would not have been honoured or that they would have freed German forces to succeed in their invasion of the Soviet Union. The preservation of the communist empire at the expense of Britain’s own is deemed a necessity.

Stalin, and all the Bolsheviks, had considered Britain their main adversary since the day of their overthrow of the Russian Republic. Stalin’s collaborations with Hitler, not limited to the pact of August 1939, make more sense in this light. All the capitalist states were to be subverted or conquered. The ideal scenario was one in which they fought and weakened each other while the Soviets grew their own capacity to dictate and threaten, as the Soviets did to the nations of eastern Europe as soon as they felt able. That scenario the pro-war forces in Britain and France delivered as though fulfilling a promise to Moscow. The Soviet perspective is routinely minimised. The same historians then assert that the Soviet Union did become a great danger as the world war ended, in Andrew Roberts’ case neatly crediting Churchill, speaking in Fulton, with prescience about the Cold War as well. Such involutions are undergone to justify the origins of the existing regime, the one established by Churchill and his comrades.

Yes

Hi Horus, have you read Conjuring Hitler by Guido Preparata? His explanation for the war solves all riddles surrounding it, I think, including the actions of Churchill and Chamberlain, and why they targeted Germany after the invasion of Poland but not the Soviet Union; that the international financiers that ruled Britain orchestrated both World War 1 and World War 2 to result in a weakened, divided continent to allow for Anglo/Jewish financier control over the continent. The only threat to British/American rule over Europe was an alliance between Germany (the brain) and Russia (the natural resources) which would have rendered a blockade by sea powers irrelevant, and everything conducted by Britain was designed to prevent such an alliance (the Mackinder thesis).

I reviewed Preparata's thesis in greater detail here: https://neofeudalreview.substack.com/p/british-and-american-machinations